by Tarik Hussein, Endeavour Energy, Australia

Growing up my home was always filled with music. My father had dozens of cassettes and CDs as he enjoyed singing Turkish classical music. My mother loved pop music and would listen to the top 40s every Sunday morning on TV. My brother would spend all day in his room with the thudding beats of techno blasting (to my mother’s dismay). Music surrounded me yet none of it felt like mine.

I was so fortunate to have parents who persevered with me through many extracurricular activities: soccer, swimming, karate, and music. I started keyboard at 6 and guitar at 7. While I eventually dropped all else, I stuck to music. Although I couldn’t recognize it back then, I’m drawn to it like it’s something essential to me.

My brother was born with cerebral palsy and growing up alongside him shaped me in ways I’m still trying to understand. I think it made me more inward and attuned to the quiet challenges people carry. I think it made me a better listener, but with my empathy more than my ears. I think it’s part of why music landed with me in the way that it did, giving me a language for what often goes unspoken.

It took me many years to actually connect with any of the music I was being taught. Most modern composition that made up the classical curriculum felt cold and dissonant to me. I never related to rock or pop music, so my only reprieve was Spanish guitar and the elegant compositions of Bach.

I couldn’t put my finger on it but for many years it felt like I was being taught a language I didn’t want to speak, but in a medium I did. That experience shaped me as a teacher. Now, I’m careful to teach my students music they connect with. Theory comes after performance, like a first language. It’s played before it’s read. I think doing it the other way around stifles your passion for music.

Everything changed for me when I first heard Chopin. It was on a cassette my mum used to help put her preschool kids to sleep. It was like discovering my native tongue in a foreign land. It had color and depth that I hadn’t heard before, and it felt like it spoke for me.

That experience has happened many times since, and I’ve seen it happen to so many of my students. I love to see someone find music that speaks to them. It’s happened with Albeniz, Bach, Chopin, Japanese game scores, Sufi music, and most recently a narrow form of Jazz. Each encounter feels like rediscovering a part of myself; and when I can play that music: being able to express it.

By the age of ten I considered myself a composer. I’d often write music as gifts, mostly for my mum, but eventually for some friends too. Sometimes I’d write when extremely ill, or when overwhelmed with emotions. It became a key part of my personal toolkit of how I’d cope with the world.

In my final years of high school I wanted to take composition more seriously, and study the highest level of music the curriculum offered. My school only offered the basic music course, but after gathering my work and making a presentation to the head of music, they agreed to let me study it one-on-one.

We had classes early in the morning or during lunch breaks. My teacher’s sacrifice was one of the kindest things anyone has done for me, and I’m still grateful till today. That course became my top mark in the high school certificate, and helped me land a scholarship to study Electrical Engineering.

People always assume that engineering and music are worlds apart. But I’ve never seen it like that. For me, music made me a better engineer by training my brain in understanding complexity, uncovering patterns, and creating structure where most don’t see it. I also love the physics of sound, and actually emailed many local universities looking for a course that combined the two. I think that Electrical Engineering was a nice compromise. Both are about propagation of waves, just in different mediums. Both have intrinsic beauty, no matter how deep you go.

My father always hoped I’d play Turkish classical music. It was the music that stirred his soul and spoke his language. He eventually found me someone who could teach it nearby, Sabahattin Akdogan. He had my uncle bring me an oud from Turkey, which is a fretless ancestor of the guitar. I studied it for three years, and it even featured in one of my high school compositions. But as much as I admire the instrument and its cultural significance, it never felt like home to me.

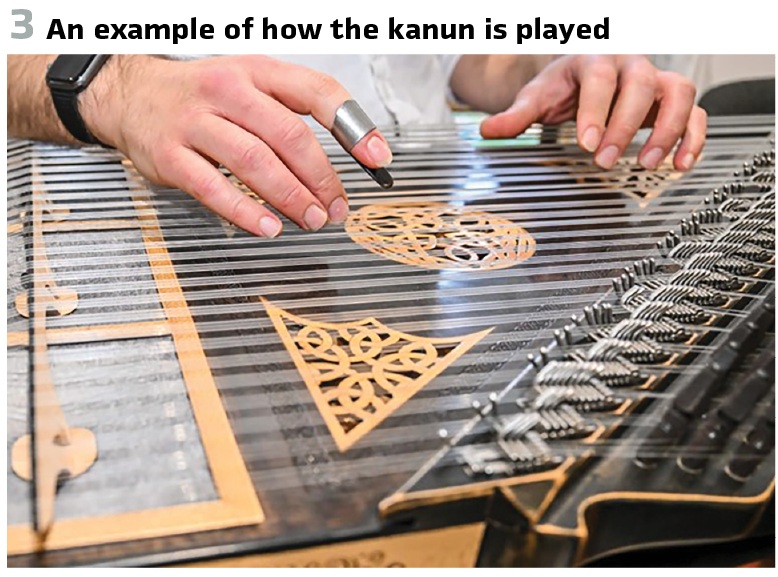

My father and I performed together in the Australian Turkish Music Ensemble for a few years. It was a relatively large choir with a small ensemble of instruments. One in particular peaked my interest. It was called the kanun (or qanun). It’s a zither-like stringed instrument played with picks or fingers, tuned while playing using little levers that have micro-tonal increments. Being the ancestor of the piano, it’s expressive, mathematical, delicate yet bold. When the kanun player in the ensemble took a break, I quickly found a way to fill his spot.

I hadn’t studied it formally like I had the previous three instruments, but I realized that I had subconsciously been trying to emulate its sound on the oud for years. When I first learnt that Indigenous Australians had a totem animal, I immediately thought about how I didn’t choose the kanun, but recognized it. It became the center of my musical life from that moment.

Being almost like a cross between a piano and an oud, it didn’t take me long to learn the kanun. I found myself performing with world-class musicians in a Sufi ensemble only a few years later, and discovering a dimension in music I didn’t learn in the western curriculum. A friend from the ensemble recorded me performing a few of these pieces, and uploaded them to YouTube. Somehow they quickly gained traction, reaching over a million views in a matter of months. Messages from strangers trickled in thanking me for helping them focus, relax, and heal. I met one person many years later who recognized me and said that he would listen to my videos when he felt overwhelmed, but was distraught when I’d taken them down. I didn’t even realize that YouTube had made them private. In that moment I realized that music wasn’t about performance, but service.

I had actually stopped playing music by this point. Music had always been how I coped and reflected. But after embracing Islam at 21, I couldn’t ignore the tension around its permissibility permeated by many mainstream scholars. I wrestled with these views for many years, and in the silence, I suffered. I fought through loss and illness without my best coping mechanism.

Thankfully I eventually found mentors who helped me see things more clearly. They showed me that beauty, when made with sincerity, can be worship. That music isn’t neutral, but like a knife, has a place in our lives. When I finally returned to the kanun, I noticed that my music had deepened. It had matured in me without being expressed through very difficult years, and was now performed with stronger intention, like a prayer.

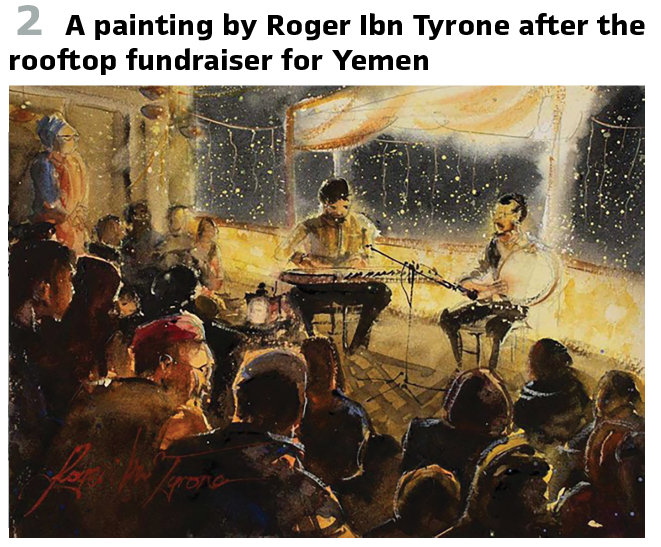

A few years later my wife encouraged me to take my kanun to a friend’s house to liven the vibe and perform a piece I’d recently learnt about Palestine. I was hesitant, but she can be very persuasive. Someone else who was there heard the performance and asked if I’d like to play at a charity fundraiser for Yemen. The atmosphere was electric, packed under a canopy of fairy lights on an inner-city rooftop. The vibe with the kanun amplified across the space left a lasting impression on everyone. A local artist was so inspired he went home and painted the scene later that night. Many items were auctioned to raise funds so I offered kanun lessons as a last-minute contribution. To my surprise, it was one of the most popular items of the night.

That’s how my first group class was formed. People were hungry for something more than music. It wasn’t just the instrument they yearned to learn, but the sense of meaning behind it.

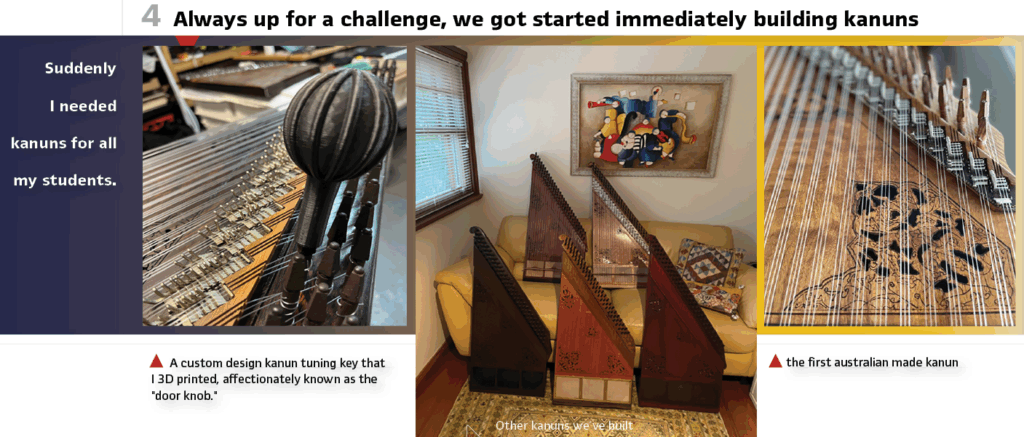

Suddenly I needed kanuns for all these students. I had 13 people with no musical background and no access to this rare instrument. I tried every kanun maker I had found over the years but they either came at an unaffordable cost or cracked and warped due to cheap packaging and materials. The Australian climate isn’t kind to these delicate timber boxes, supporting literally tons of pressure exerted by 78 strings onto a thin skin-like membrane. I had repaired my own kanuns over the years, but I needed a more permanent solution if these classes were going to be feasible.

That’s when I turned to my father-in-law, a budding luthier (instrument maker), and asked if he’d be interested in trying to build kanuns together.

Always up for a challenge, we got started immediately. First, we had to dismantle some of mine, to reverse-engineer the internal structure. I quickly realized we weren’t just copying it, we were innovating from the outset. We used Australian timbers, re-enforced the body and had my mother-in-law (a visual artist) designing unique patterns to carve into the soundboard.

We’ve since built eight kanuns, each taking many months. One of them is even commissioned by the Powerhouse Museum as an object of cultural significance.

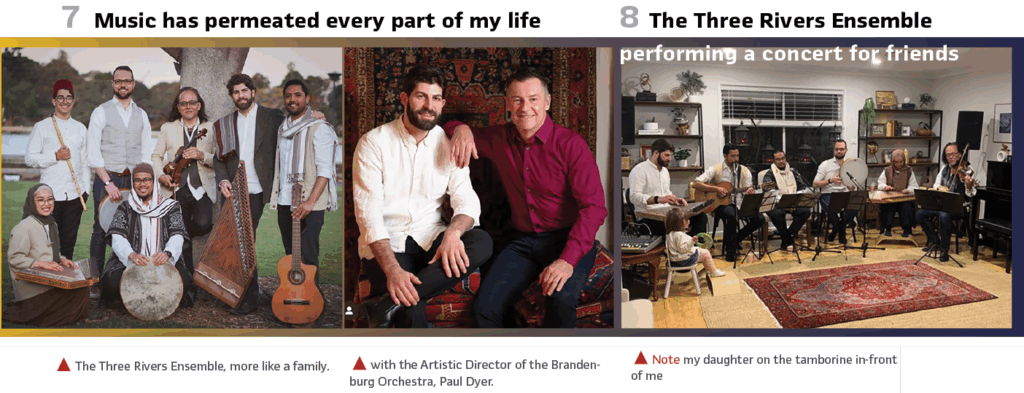

That spirit of collaboration shaped everything that followed. My wife helped create a social media presence for me under the name KanunGuy. That identity led to many new opportunities, collaborations and what felt like a full-circle moment: performing with the Brandenburg Orchestra. They asked me to join a concert called Ottoman Baroque, a fusion of ancient music from the east and west. A blending of the two worlds I felt I’d come from.

Lately, music has permeated every part of my life. I formed an ensemble: The Three Rivers, with my closest friends. We love to rehearse with our kids joining in. For them it’s not just an anecdote, it’s like a rock in their lives. Playing music with our families reminds me that I don’t play music to perform. It means much more to me than that. I want our kids to grow up knowing that beauty matters. That making something real with care, with intention, is one of the most human things we can do in an increasingly digital world.

The idea of craft led my wife and I to establish something more than a music school: Rumi School of the Arts. A not-for-profit organization that can be a platform for cultural expression, to support all forms of craftspeople: musicians, visual artists, martial artists, woodworkers, calligraphers, even cooks. Somewhere where adults and children interested in carrying forward sacred traditions and crafts can come to rediscover the beauty of discipline and creation.

It hasn’t been easy finding the right teachers, people not just skilled but like-hearted. People who see art as a form of service. One of the pioneers in this space is a dear friend: Peter Gould. He’s a creative force and a generous soul. He’s shared my work with his communities, opened doors and helped me realize that craft, when nurtured, becomes community.

I work full-time as a protection engineer. I build instruments in the garage. I teach on weekends and rehearse on weeknights. I don’t separate the various parts of my life but let them overlap. Whether it’s music or engineering, the principle is the same: to bring things into balance. To listen carefully and to protect what matters.

Despite being a performer, the goal is never to shine. Instead, I believe everyone should focus on being real. Being consistent, being present and being grateful. Your steadiness could be the thing someone else needs to get through difficult times. This is what I’ve learned from my family, my friends, my teachers, my students, and especially my wife. From my faith, my career, and my music. To me, it’s always been more than music

Biography:

Tarik Hussein is a Senior Protection Engineer at Endeavour Energy, where he focuses on technical secondary systems leadership in the transition to a net-zero grid. Outside of engineering, he is the founder of Rumi School of the Arts, a not-for-profit school dedicated to teaching traditional arts and crafts. He lives in Sydney and divides his time between his career, his music, and his family, integrating them where possible.