by Scott Cooper, OMICRON electronics, USA

Why does one commit the thought, time, energy, and money required to participate in offshore fishing?

As most fishermen,I started fishing with my father as a child. My first saltwater experience started with snorkeling for lobster in the Florida Keys backcountry on a very small 3m inflatable boat with an outboard motor. The “backcountry” consists of hundreds of small islands and inter-connected shallow bays. I was exhilarated by adventures with frequent summer thunderstorms, getting lost, running aground, and even breaking down.

A few years later, our family purchased a 6m boat powered equipped with a larger outboard, a marine VHF radio (line of sight, 2-way marine radio), fish finder (Sonar for finding depth and locating structure or fish), and electronic navigation (LORAN) that allowed us to fish offshore. Each year we would travel to the Florida Keys in May or June to catch dolphinfish (aka mahi mahi or dorado) on their Spring migration from the Caribbean to New England. Although the waters of the Florida Straits can be rough and I was prone to seasickness, I was always enthusiastic about going. In time, my seasickness faded, and I settled into a life revolving around boats and the water.

What is “deep sea fishing? Definitions vary, but in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico and Straits of Florida where I mostly fish, it means fishing away from the effects of land. Offshore fish dwell in three zones:

- The pelagic zone consists of open ocean water near the surface. My target species living in this zone in my fishing areas are Dolphinfish, Wahoo, and Tripletail

- The bottom zone of course consists of water near the bottom. My target species for this zone are Hogfish, Groupers and Snappers

- The midwater zone consists of water between surface and bottom waters. My target species for this zone are Amberjack, King Mackerel, and Cobia

How does deep sea fishing work – what is the specific process that you follow? The steps are simple:

- Identify the target species

- Find out when the fish are biting

- Find the fish,

- Present a bait that the fish want to eat,

- Hook the fish, and

- Get the fish to the boat

Somewhat like the game of golf, the underlying principles are straightforward but require a lifetime of effort to master.

Identifying the target species is the critical first step as it determines everything else.

However, an experienced fisherman always hedges their bets. While trolling for pelagic fish, I always have deep dropping gear on board in case fishing is slow or I find particularly enticing bottom 700+ feet below. While bottom fishing, I always set one line at the surface as you never know when a very desirable surface-dwelling species will decide to investigate your activities.

How do you know when the fish are biting? Like people, fish do not eat all the time. For most fish sought by recreational fishermen, water movement is the biggest factor. For pelagic species, large oceanic currents like the Gulf Stream are like a river flowing in the ocean, attracting, or even corralling smaller fish and consequently, the larger fish that prey on them.

The other major source of water movement offshore is tide. On the bottom, this moving water brings prey to waiting predators. Tide is the movement of water due to changes in the gravity exerted by the moon and sun. Weather conditions can also affect currents, sometimes quite strongly. Ambient light levels due to time of day, cloud cover, or moon phase also affect feeding habits.

Finally, like many other living things, the moon’s phase affects fish behavior and feeding habits. Changes in weather also affect feeding habits. For example, stormy weather approaching intensifies their desire to feed. Expert anglers keep careful logs to identify trends.

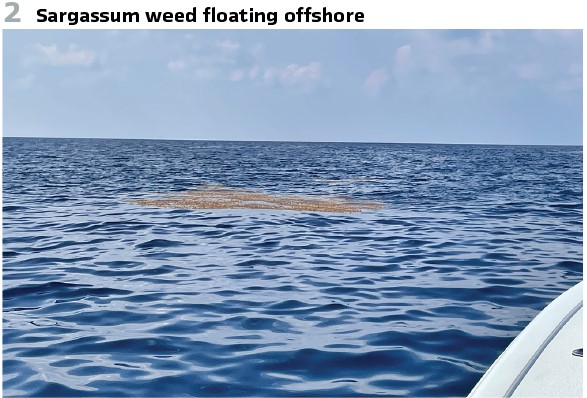

How do you find fish in a vast sea? Fish always seek “structure.” Structure offers protection from predators and/or attracts prey. In the surface zone of a pelagic environment, structure is like an oasis in an endless desert and can take many forms. In tropical and sub-tropical waters, the most prevalent structure is sargassum, a coarse alga that floats in small clumps, large mats, or in lines stretching for miles.

Other types of structures can be a floating tree trunk washed into a river far away, offshore petroleum drilling structures, or debris from human activity such as wood pallets or buckets. This floating structure provides shelter to juvenile fish and small crabs, followed by progressively larger fish to apex predators such as the mako or tiger shark. Another type of structure found offshore are currents or collisions of currents that cause upwelling of nutrient rich water or cause color, clarity, or temperature changes. These changes can attract or coral smaller fish and thus attract larger predators. For offshore bottom dwelling fish, structure can be a rocky bottom with drop-offs, holes and ledges, soft mud for some species to burrow in, rocky holes and water flow from natural freshwater springs, or objects left from human activity such as pipelines, shipwrecks, or artificial reefs.

Artificial reefs are clean concrete or steel structures installed on the bottom by fishery managers to increase fish populations. Fish move between all types of structure according to the presence of prey, their desired water temperature, salinity, water clarity, or life cycle.

Just as the very first fishermen did a millennia ago, to find species dwelling near the surface of a pelagic environment we depend on the best ocean fishermen of all: Sea birds. To the practiced eye, the species, number, and activities of birds reveals much of what is going on below them. A solitary frigate, circling high above the water nearshore is waiting to ambush other seabirds returning from the sea, forcing them to give up their stomach contents. Offshore, they are likely following a large predatory fish. 3-5 birds circling and diving are catching smaller bait fish driven to the surface by a small number of predators from below. Large groups of diving birds indicate a large school of bait being preyed upon by numerous predators. Birds meandering around surface structure is a sure sign of predatory fish in the area. Numerous birds uniformly flying in one direction indicate the direction to a feeding event. Technology such as electronically stabilized binoculars or marine radar is now used to find birds at distances far greater than natural human sight. With radar, depending on the operator’s skill, the unit’s output power, antenna type, antenna height, and surrounding wave height, a fisherman can locate groups of birds several miles away. Technology does not stop there however, as subscriptions are available that allow monitoring sea temperature changes, weed patch location, and chlorophyl concentrations via satellite link in real time.

Finding bottom dwelling fish requires identification of the depth and bottom composition. For centuries, this was accomplished by “sounding,” or dropping a specially shaped weight on a line to the bottom to identify depth and, by observing what comes up on the weight (nothing, sand, mud, shell, gravel), bottom composition. This effectively limited the effectiveness of recreational bottom fishing offshore until the 1970’s when the first electronic recreational bottom sounders appeared. These primitive early units worked by using a DC motor rotating a light assembly against a dial printed on the instrument’s face. When the rotor was at 12 o’clock, a short pulse was initiated (usually 200Khz). This pulse was applied to a specially designed speaker/microphone in the bottom of the boat oriented towards the bottom called a transducer.

The resulting sound travels towards the bottom at the speed of sound. When the sound wave encounters targets such as the bottom or vegetation or fish, some part of the transmitted pulse is reflected back. When the reflected pulse returns to the transducer, a pulse is generated which illuminates a LED on the rotor. The rotation speed of the rotor, the distance the rotor travelled between the pulse transmission and the return echo was used to indicate the depth of the target against the printed dial. Ranges were varied by changing the motor speed. Bottom hardness is proportional to the thickness of the returned echo. Fish could be identified by smaller echoes above the bottom.

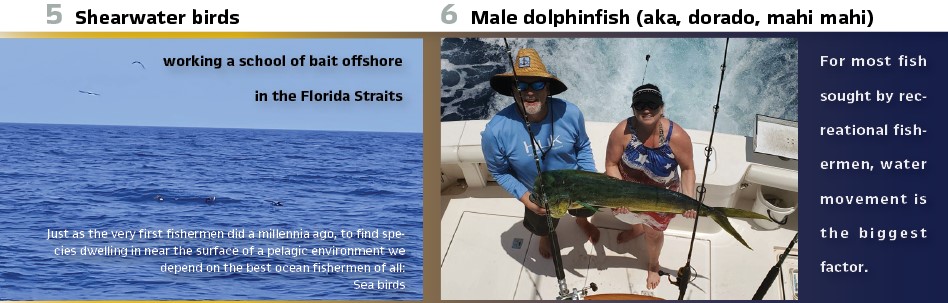

This early technology was followed by a rapid progression of innovations such as a graph generated by burning a paper trace, similar in operation to an early Honeywell Visicorder used in industrial applications. Eventually, like many other technologies, digital signal processing and on-screen rendering have revolutionized fish finder performance. Perhaps the largest advance in fish finding technology is Compressed High Resolution Radar Pulse, or CHIRP. Instead of a single frequency pulse tone, a range of frequencies are transmitted in a series of short pulses. This results in more energy transmitted into the water and much greater resolution. State of the art equipment today can produce a 3d graph of bottom structure and fish that can be installed on a recreational boat or purchased as an electronic chart layer.

Of course, once productive areas have been found, being able to return to the same spot again is critical. The first widely utilized electronic position equipment by recreational anglers was LORAN, which consisted of a network of time synchronized transmitters along the coast, these devices calculated the boat’s position from the differences in arrival times from different transmitters, measured in milliseconds. These times could be used to return to a location (within 100m or so), and corresponding lines, or TD’s, were printed on charts to facilitate conversion to Latitude and longitude. Since then, GPS and the Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) has facilitated near pinpoint position accuracy and repeatability while electronic charting provides a very efficient way to interface with the data. Off the water, specialized software and web services now facilitate the analysis of climate and oceanographic data to predict where fish will be and when they will be there.

How do you present a bait? First, the boat has to be positioned correctly. When fishing for surface dwelling fish, it could mean positioning the boat close enough to bird activity to attract the predators, but not so close as to scatter the school of bait. When bottom fishing, it means positioning the boat so that the bait can be presented very close to the underwater structure where the target species are. Once the boat is in position, bait presentation is largely deception. The object is to make the fish believe the bait you are presenting is a natural prey. Based on the conditions encountered, a myriad of possibilities exist for doing this. Technology has improved this process as well such as with braided spectra fiber lines which offer unprecedented strength and smaller diameter for a more natural bait movement. Another notable innovation is the circle hook. Now mandated by many fishery managers for all natural baits, the circle hook facilitates the safe return of fish not kept due to size/species regulations to the ocean. The hook is designed to prevent the fish from swallowing the hook, instead hooking the side of the mouth and facilitating easy hook removal without injuring the fish.

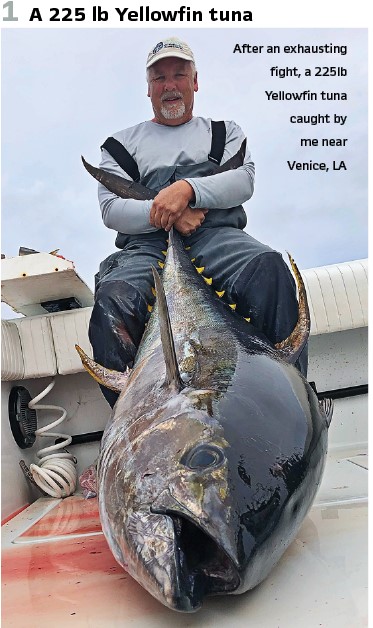

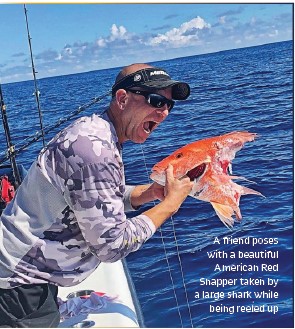

Once hooked, how do you get the fish to the surface. It sounds straightforward, but like most other elements of sportfishing, it’s frequently harder than it first appears. For larger fish such as a yellowfin tuna, marlin, or other large pelagic, this stage can take an hour or more and involve considerable physical effort. Of course, any mistakes in preparation or execution are rewarded with a sound every fisherman knows and dreads-a snap, rattle, and sudden slack in the line indicate a parted line or other tackle failure. Even smaller fish can put up quite a fight by either retreating to rocks, hopelessly snagging the line or by powerfully swimming away, jumping wildly or head shaking. As the fish fights, the hole created by the hook opens wider, and the jumping and head shaking can easily put enough slack in the line for the hook to simply fall out. In addition, larger predators are attracted to the struggling fish on the line. Sharks, barracuda, and goliath grouper readily take advantage of a fish trapped on a line. Every offshore angler can tell the story of reeling a fish of a lifetime in and seeing a very large, very excited shark appear out of the blue, heading for his fish at full speed. The angler aggressively pulls the rod, moving the fish just clear of the shark as it goes by. Pectoral fins down for maximum maneuverability, the shark changes direction near instantaneously for another try. The anglers rod tip is already up so there is nothing to do but watch as the shark grabs the fish, tearing it from the line or simply biting it in half-millions of years of evolution on display. As formidable as they are while fishing, sharks are not the biggest challenge to getting a fish to the boat. Occasionally a porpoise pod appears, and the fishing is over. Highly intelligent and powerful predators, individuals patiently wait for fish to be hooked then politely take turns effortlessly removing the fish from the line as it is raised, deftly avoiding the hook. Sometimes mothers can be seen teaching their young to do it. Even moving the boat several miles does not help. Once identified as a food source, the pod follows the boat and usually arrives at your new spot within minutes of your first line entering the water.

So why does one commit the thought, time, energy, and money required to participate in offshore fishing? I’ll never come up with a reason that would satisfy a psychologist or an accountant. As an outdoorsman, I enjoy being in the wild and seeing the sea turtles, birds, and of course the fish. For the adventurous side, there is equipment breakdown, rough water and even storms. As an engineer I suppose I appreciate the problem solving and technology. On another level, perhaps finding a wild place to enjoy by ourselves in an increasingly crowded Florida is a nice break.

Biography:

Scott Cooper has over thirty years of experience in a variety of roles including power plant operations, substation commissioning, application engineering, project management, and technical training. He is a member of the IEEE and is active in the Power System Relaying Committee where he works on standards, guides, and other works related to system protection. He has also authored and presented numerous conference papers and magazine articles on protection. He currently works as the Application and Training Engineer for OMICRON in Saint Petersburg, Florida, USA.