by Kate Murphy, Vector, New Zealand

Kitesurfing is an exhilarating sport which harnesses the power of the wind to ride along the water and to jump into the air.

The power system is the gear in its entirety – it consists of wind, a kite, lines, a bar, a harness, a board and of course – a person!

The control system is the interaction between the person, the board, and the bar. This manages the power, direction and resulting speed of travel for the Kitesurfer.

Kitesurfing is also a high-risk sport, as controlling the immense power of the wind while being tied to a large kite can be dangerous if things go wrong. The systems we use today have built in layers of safety protection, to prevent and/or minimise harm, which I will describe in this article.

How did I start:

I’m originally from Cork, Ireland, and I moved to New Zealand in 2015. I love Type-A active fun and the great outdoors, so I immediately fell in love with the New Zealand and all it has to offer.

Kitesurfing has always been something I wanted to try, it fascinated me. How one person can be in command of the power of the wind, riding the waves and flying high through the air. It looked so dangerous but liberating. Now in Auckland, the city of sails, I found that there were so many great kiting spots available no matter the wind direction, so I had to learn to kite, I had to try it.

The fastest and safest way to start kiting is through lessons, which I did over a 4-day Easter Break in 2015. It was a steep learning curve, a small mistake can be punishing, but once I was able to stand up and travel upwind it was one of the best sports I’ve tried.

Relating Kitesurfing to work:

The concept of the system used for Kitesurfing is very relatable to aspects of my day-to-day work, and throughout this article I will do my best to describe the sport and its components in Engineering terms. I hope you enjoy…

It all starts with wind. Wind Speed is the primary energy flow that is harnessed by the Kite. It is directly related to output power of the system – how fast you travel and how high you can jump to do tricks. The tides also impact relative wind speed when on the water. As kitesurfing is best with an onshore breeze, due to safety reasons, kiting on an outgoing tide generates more power.

The kite is the power converter, which converts the wind energy into usable kinetic energy for kitesurfing. Similar to how a wind turbine converts wind into electrical energy. My favourite kite is my 9m C-type kite, which has an inflatable leading edge. I find this size best suited for my weight & height, and a good range of wind conditions I typically go out in from 16 – 30km/hr. On lighter wind days, I would take the 12m out.

Kite size and shape relates to the rated power of the converter. The kite size is a set value, however the shape a variable, and is controlled by pulling the bar away or towards one-self. When the bar is pulled towards your body, the outer strings become more tense and the kite becomes more of a “C” shape, which increases its power capacity. When released and pushed away from the body, the outer strings release and the kite becomes flatter and less powerful.

The board and Kitesurfer is the load, and there needs to be sufficient power production to meet the demands of the load. This load also has a slight varying demand based on the angle of the board against the water and position of the rider.

The position of the Kite in the wind window, I would relate this to Voltage. Depending on where the kite is positioned, the power output is either increased or decreased to meet the demand of the load.

Response Time: This is the delay between sending a signal from the bar to the Kite when the person is issuing commands, for example – steering the kite. The bar requires pressure on the left or right to steer the kite through and around the wind window. When learning, I found through a few crashes and body drags along the beach, that there can be a significant delay in response time between putting pressure on the bar and the kite acting in the desired way. If you – part of the control system, don’t plan for the time delay, it’s easy to overdo the action and crash.

Inrush Current: Starting up on the water draws a lot of inrush to overcome the stationary starting position. To get up and ride, the kitesurfer needs to swoop the kite across the power zone of the wind window. This swoop creates a surge which is enough power to overcome the initial resistance of the kitesurfer and allows the kitesurfer to stand up on the board and move off. Once up, the kite is parked at a suitable power position that can sustain the load requirements, at a desired speed and direction. If the kitesurfer draws too much inrush – this can result in a faceplant, and the system could fall-over. The inrush needs to be carefully managed with good kite control.

Variable Generation: The wind is a variable source, and many New Zealand kite spots can be prone to unexpected gusts. On each gust the system of Kite & person can go out of balance – which in my experience, if too imbalanced, ends up with me crashing and drinking a heap of sea water. When this system collapse occurs, I have to blackstart to get going again. On the other hand, when the wind suddenly falls, it can stall the kite. In these instances, I need to add more power generation capacity – by swooping the kite across the power zone and moving the bar. I have often done this for the wind only to pick up again suddenly to make the system overpowered. It’s easier to maintain system balance with a consistent wind, and therefore that is the preferred kiting condition for most.

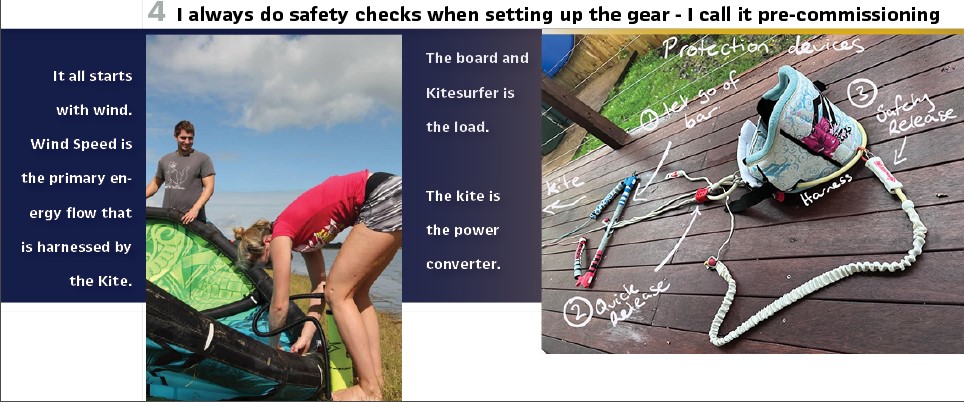

The Protection Devices: There are three layers of protection in my Kite system set-up, although all require a manual operation to work.

The first layer is to simply let go of the bar. When being overpowered by the wind and when out of control, letting go of the bar will depower the kite and it should fall to the ground/ water – if the wind isn’t too strong. In about 90% of all cases, this is enough to get out of a dangerous situation and stop the kite.

The second layer of protection is the quick release. If letting go of the bar does not work, then operating this will almost fully detach your kite from your harness, apart from one string remaining – the safety. This safety string will pull the kite into a flag and it should lose all of its power and flop to the ground / water. I have used this in quite a few situations, an example being where my bar had become wrapped around the string on one side of the kite, which caused the kite to remain powered up and loop violently out of control.

The last layer of protection is activating the safety leash. This is used on the rare occasion when all other protection layers are not an option or have not worked. This is the last system that should be used as you will most likely lose your kite and it can become a hazard to others if flying onshore – potentially flying into powerlines, traffic, people. Fortunately, I have not yet had to use this feature on my own gear, but I have friends that have had to and it’s never a good situation when this is required.

Other safety aspects of going kiting is choosing conditions and locations suited for your ability. A key consideration is ensuring that there is an onshore wind direction, so you don’t get blown out to sea. Another is understanding the area – where it is safe to launch, where the gusts tend to be due to the surrounding land, water depth, knowing where rips and currents are. All of this has worked for me so far, which is why I find kitesurfing really enjoyable. The kiting community is also very friendly, whenever I turn up to a new spot on a good wind day, I can always find someone who knows the area and have a chat to them about it.

Good asset management is a priority, not only because kite gear is expensive to replace, but because any equipment failure can leave you in a tight spot or in danger. After witnessing some scary situations of kite safety systems failing for others, it highlighted to me further just how important it is to test and maintain your gear. Just like at work, it’s very important to test & maintain Power System equipment, especially where safety is concerned.

I always do safety checks when setting up the gear – I like to call this pre-commissioning. Once pumped up and lines connected, I do visual point-to-point testing on lines to ensure they are not connected to the wrong part of the kite. And, importantly, I operate and test all of the protection devices on the system to ensure there’s nothing stopping them. I have found my quick release jammed before, due to environmental corrosion – so it’s a must-do to check these, your life can depend on it. Once the pre-commissioning checklist is complete, it’s time to get the kite flying, the launch. After a successful launch, all commissioning tests are passed – it’s out to sea to play on the water. The best part.

How do I kite with work?

My ideal time to kite is on weekends, however I enjoy midweek summer sessions when the wind condition lines up with work finishing. The wind is best when the sun is out, as it can drop off when it gets dark due to the effect of the land cooling.

Unfortunately, it’s been a while since I have had the chance to go out on the water to kite but am hoping that by the time you read this article I have been out. The New Zealand summer of 2023 so far has seen unprecedented rainfall, flooding and a tropical cyclone named Gabrielle which has caused extensive destruction across the Country. As I write this, there is still a national state of emergency, thousands of people without homes due to flooding and landslides, and even more people without power. The conditions this year have been wet and extreme and sadly the timing between work and play have not lined up with suitable kitesurfing wind for me. I did see one person kiting the cyclone weather, it was amazing and also crazy to witness as they got some serious big air jumps in. I don’t have the experience of a small enough kite to go out in those conditions yet, but maybe one day! I’m looking forward to getting out again soon and improving my air skills.

Biography:

Kate Murphy is an Engineer who has immigrated from Ireland to New Zealand. Her experience ranges from renewable energy – developing solar PV and grid-scale battery storage systems, to electricity network operations and management. She is currently the Electricity Operations Planned Work Manager at Vector, New Zealand’s largest distributor of electricity. Kate is also an active IEEE member and is Chapter Chair of IEEE PES New Zealand North. Kate is very active, and outside of work, loves spending her time outdoors and in the ocean.