by Robert Frye, Tennessee Valley Authority, TN, USA

I have always been a builder, and I love working with my hands. In fact, my wife nick named me “Builder Bob.” Although I have performed many home renovation projects, my passion is for bigger, more complicated, industrial projects.

Up untilabout the midpoint in my electrical career, I was mostly able to satisfy this need to build through working on projects for my employers. On the side, I was able to build a couple of roads, install a large water main and fire protection system, construct an underground, 5 kV power distribution system, and help rebuild an overhead power distribution system feeding a church camp. Later, as I moved into the higher levels of engineering and management, I was distanced from the actual work, and this really left a void in my heart, my brain, and in my creativity. I really needed to resume building things again!

In June of 2000, my wonderful wife, April, held a surprise birthday party for me at the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum. During the party, I was given the opportunity to drive a 1940s vintage diesel-electric locomotive for several miles. At that point, I was hooked! I continued to visit and then volunteer at the museum and gradually moved in to train operations and then into locomotive engineer training.

This time at the museum was golden because I was learning an entirely new field. Everybody at the museum knew more about railroading than I did. I had no preconceived ideas about railroading because I didn’t know anything about the industry, and this gave me the opportunity to learn from each and every person at the museum. It soon became obvious I wasn’t the only degreed professional volunteering at the museum. There were civil engineers, mechanical engineers, welding engineers, retired railroad professionals, ex railroad employees, businessmen, master craftsmen, and others to make the museum a healthy and thriving place.

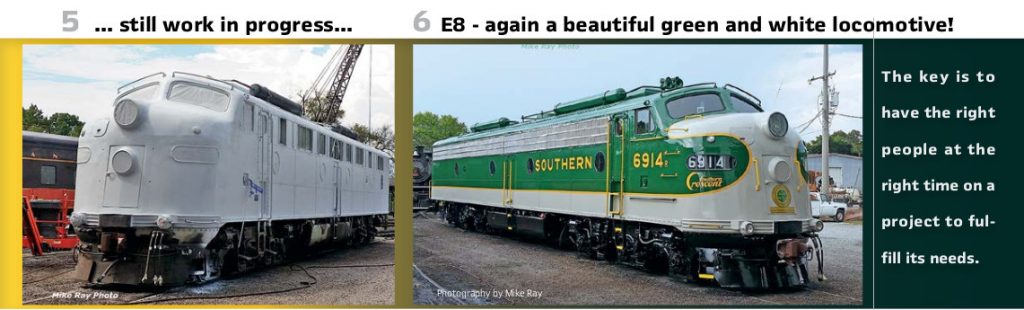

Soon after I joined the museum, they began their first, complete steam locomotive restoration. In other areas, they restored passenger cars and cabooses and performed running repairs on their operational equipment. Up until this point, the museum had never performed a total restoration on a diesel-electric locomotive.

In 2003, my wife stunned me again. She had been accepted in a graduate program in Atlanta, Georgia and was going to be living 120 miles from home for four years! What was I going to do with all this free time? Being a builder at heart, I thought the museum might have something I could do with my idle hands. I went to the railroad shop and asked the foreman if there was some way my electrical skills could help the museum. He suggested I could rewire the E8. Not having any idea what an E8 was, I had to go look and see what he was talking about.

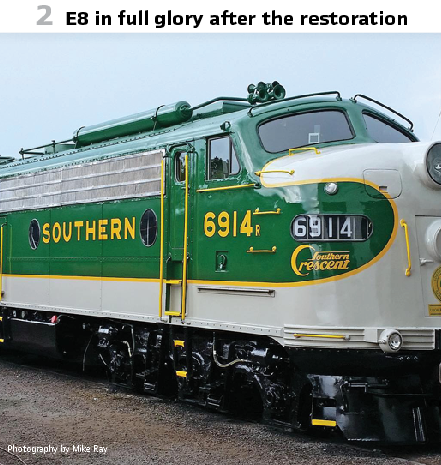

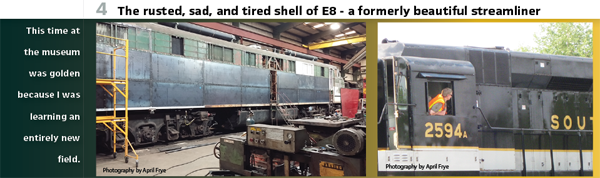

The E8 was a rusted, sad, and tired shell of a formerly beautiful green and white streamliner locomotive manufactured by General Motors, Electro Motive Division in 1953. It had been purchased by the Southern Railway in Atlanta, Georgia for use in its famous Southern Crescent train that operated between Washington DC and New Orleans, Louisiana. It was numbered 6914.

The locomotive measures 70 feet long and weighs 316,000 pounds. It has two, 1,200 horse power engines with each driving its own generator. Each generator supplies power to drive the motors on two axles under the locomotive.

The front engine and generator supplies power to the front two axles and wheels while the rear engine and generator supplies power to the two rear axles and wheels. The front two axles and wheels are combined with a non-powered axle and wheels to form a “truck.” The same is true for the rear axles and wheels. In its day, the locomotive was very unique because of having two engines and generators. It’s essentially two locomotives on one frame. The engine governors are electrically tied together to make both power plants act as a single unit.

In the 1980s the Southern Railroad exited the passenger service and sold the locomotive to Amtrak who continued to operate the Southern Crescent as the Crescent. Later, she was sold again to New Jersey Transit and finally sold to a junk yard in St Louis from where the museum purchased it. Over its life, the locomotive plied millions and millions of miles safely pulling passengers throughout the nation.

Looking at the locomotive, I knew this was just the kind of project my brain and hands needed. Naïve about the astronomical amount of work and skills required for locomotive restoration, I agreed to do it. Right away, two other volunteers joined the project, and the three of us became the core team that are still together today.

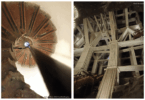

Our first task was to create a safe work environment within the locomotive, which took several months. Clutter, dirt, and spare parts were removed, work lights installed, and scaffolds built. There were so many loose parts in the locomotive, we had to requisition a section in our warehouse just to create a safe storage place. Not knowing much about E8 locomotives, we weren’t even sure if all these parts belonged to the locomotive or not!

As work continued, more folks became involved, we gradually learned the locomotive’s seemingly endless needs. The more we rehabilitated, the more problems we found needing repair. This was very disheartening. The museum’s President, Bob Soule, would visit us occasionally. I can still remember his words “You are doing a great job. Just don’t stop!” I believe one has to think of these projects as a long series of small victories rather than a single, final, glorious victory.

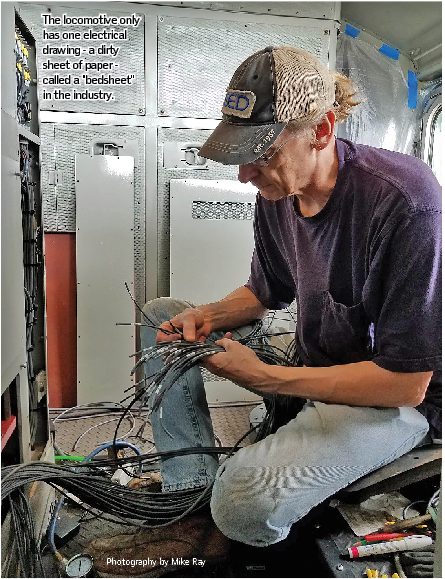

The locomotive only has one electrical drawing. Its an unwieldy tired and dirty sheet of paper measuring 4’ wide and 23 feet long! In the industry, it’s called a “bedsheet.” One small area of the drawing is a schematic, and the rest is a physical wiring diagram with text oriented in four different directions: normal, upside down, vertical up, and vertical down! When the drawing is arranged to align with the locomotive, the text is in the correct orientation regardless of where you are standing within the locomotive. To preserve the drawing and allow it to be easily modified, I redrew it in ACAD. This required six weeks of tedious drafting and understanding railroad drawing paradigms.

Even though I only agreed to rewire the locomotive, I quickly realized years would be required to complete the locomotive and many tasks needed to be completed before we could begin wiring in many locations. Also, the project needed a leader, jack-of-all-trades, and a champion. I fell into this role because I knew if I left, the project would die, and all our efforts would be wasted.

You have to remember the E8 is in a museum because it was obsolete as far as the manufacturer and the Southern Railway were concerned. This meant many parts were difficult to find or simply not available. We scavenged the country looking for parts. Sure, we used the internet, but we also used lots of windshield time and hotel rooms. When all this failed, we had to make the parts.

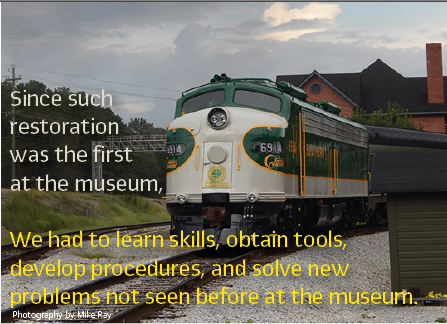

Since this restoration was the first, complete diesel locomotive restoration performed at the museum, we had to learn skills, obtain tools, develop procedures, and solve new problems not seen before at the museum. For example, we had to remove the trucks from under the locomotive and load them on a flatcar to be sent away to the repair shop. Trucks are the assemblies of wheels, motors, and frames the locomotive sits on. This task sounds easy enough, but we had never lifted the E8 before, let alone wrestled two, 50,000-pound sets of trucks from under the locomotive while it was still up in the air! Plans were made, rigging designed, jacks inspected, and slings & shackles were purchased. Finally, the day came. We jacked the locomotive to clear the trucks, rolled the trucks from under the locomotive, lifted them with our historic derrick and placed them on the flatcar. We did it! Big projects are like this. Some days you leave the project beaming with victory. Other days you move one step forward then take four steps backward.

In all restoration projects, you have to ask yourself; what’s your objective? Do you want to end up with a display piece, a barely running locomotive, or an every day runner? The answer to this determines the amount of work you do and the solutions you chose to move forward. We wanted a reliable locomotive we could run every day with no fear of breakdowns.

Locomotive brake systems are differentiated by their model number. The smaller the number, the older the system. The E8 originally had a Number-24 (#24) brake system in the cab for the engineer to use to control the speed of the train. This system was popular in the late steam engine and early diesel locomotive days but is certainly obsolete by today’s standards. In addition, federal regulations require the #24 brake system to be inspected frequently, adding to the ongoing cost of the locomotive. So, we wouldn’t want this in a daily runner.

The #26 brake system is the most common in modern locomotives. We initially chose this system for our locomotive if we could find an ergonomically proper location near the engineer’s seat. The brake controls absolutely needed to be easy to operate. This was a problem. We tried mock-ups and prototypes, and nothing was satisfactory. The engineer would have to be a contortionist to use it. So, we abandoned the #26 brake system.

Next, we investigated the #30 brake system. The #30 controls are mounted in a desktop panel exactly where the engineer needs them. With a five-year maintenance interval, this seemed like a win. We faced another decision. Do we continue with the historical fabric of the locomotive or make that good, reliable, everyday locomotive we wanted? We chose the latter. Now, we had to create a place to mount this new set of controls.

We looked at modern locomotive designs using the #30 brake for ideas. Yes, this would work in our locomotive, but we would have to make a desktop from scratch. Beginning with scrap plywood for a prototype, we placed several of our engineers in the seat and said, “Try it out and see what you think.” We took comments and made adjustments. Once we were happy with the dimensions, we built it with steel. One more item off the list and another victory for us.

Other items followed along in a similar manner: the rest of the cab, engines, generators, radiators, roof fans, dynamic brake system, couplers, fuel tank, frame, sides and exterior body, windshields, cab heaters, defrosters, electrical cabinets, air brake system, headlights, doors, windows, etc.

I am occasionally asked what kept us going through the 16 years we spent working on the locomotive. That’s a hard question. The answers are as varied as the people who worked on the project. I can only answer for myself. To begin with, it’s a little hard to think I’ve actually dedicated a big percentage of 16 years of weekends, days off, and evenings to the locomotive.

In fact, my personal record keeping indicated I logged nearly three man-years working, scheming, scrounging, cajoling, and planning on the project! One of my main drivers was not wanting to turn the locomotive into a parts kit. A Parts Kit is where a person or team full of excitement begins a restoration project. As part of the project, they have to disassemble things. This is even exciting because they are seeing rapid progress and rapid changes. Once everything is disassembled, the long, slow battle begins of making all those old, worn-out parts into shiny new parts. People can quickly become disillusioned and quit the project and leaving no documentation indicating how things went together. They’ve turned it into a parts kit. Many preservation projects throughout the world suffer this fate.

Locomotive restoration projects need people. That sounds like a trivial statement, but I assure you it’s not. I once heard someone say if they had 200 people on a project and if none of them had a skill such as electrician, welder, machinist, engineer, pipe fitter, etc., he couldn’t use most of them. So, the key is to have the right people at the right time on a project to fulfill its needs.

As I look back over the 16 years of restoration, we had over 100 people helping. Some were working from the very beginning. Some joined along the way, and some only worked a day or two. We even had a few contribute by simply making a suggestion or writing an email or perking us up when we were down. Others helped, and they never even knew they helped. Most were volunteers. Without their help, E8 locomotive #6914 would still be in the shed, forgotten and rusting away.

This has been a wonderful project, and I have been so lucky to be a part of it.

Biography:

Robert Frye, PE, is a Senior Program Manager in the Transmission Asset Management Department at the Tennessee Valley Authority in Chattanooga, TN. He is responsible for protective relay asset strategy. Prior to that, he was a Principle Engineer in the Protection & Control dpt., a Specialist Engineer in the System Protection & Analysis dpt., a Project Manager over the Conservation Voltage Reduction program in the Demand Response Department, and he was a System Engineer at Watts Bar Nuclear Plant. Robert is a registered professional engineer in Tennessee, and he has a B.S.E. degree from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. He was recently selected as TVA’s Engineer of the Year for 2016 and a top ten finalists for the Federal Engineer of the Year for 2016. He is a member of the IEEE PSRC Committee.