by Nicolas Soellner, Germany

It all began with taking a dinghy sailing course…

“Why not give it a try?” I thought, and to cut the story short: it was a hobby that had been looking for me.

Many times, already I have crossed the Atlantic Ocean by plane, for business and pleasure, as a lot of us do. It just takes a couple of hours to cover thousands of miles, no preparation necessary, and seldom does one waste any thought on how to get to the other end. The biggest challenge sometimes seems to be to locate the proper check-in counter at the airport. By coincidence, I currently find myself on board a flight heading back from Canada to Germany while I started writing these first lines.

Not a long while ago, I happened to be in the same area, right in the middle of the Atlantic, a couple of thousand miles away from the next shore, also heading eastbound towards Europe. Yet at water level instead of 30.000 feet of altitude, with a cruising speed of something in between 10 and 20 nautical knots instead of 800 km/h and enjoying the comfort of a hot cup of tea on the deck of a cold and wet sailboat, instead of a cozy plane seat with full board service.

Why on earth did I end up there, you might wonder? Well, be assured to find yourself in a good company with the blank looks of many of my friends and relatives, and sometimes even myself. The thought of voluntarily spending money and using up most of your annual leave to cross the ocean in a constantly rocking and rolling sailboat, fully exposed to all elements, with very little comfort and a rough sleep for weeks, appears odd to most people. And it probably would also have to me, if you had asked my younger self just 15 years ago.

Some things in life just happen by chance yet have the power to massively influence the future. I have always liked being around water, but I never wanted to become a sailor. In fact, sailing as a hobby wasn’t on my radar at all, until a study friend enthusiastically told me about the fun he had when doing a beginner’s dinghy sailing course at my local university at a lake nearby. “Why not give it a try?” I thought, and to cut the story short: it was a hobby that had been looking for me.

Sailing was so much fun, enjoyment and challenge at the same time. It didn’t take me long to finish all the courses, find a permanent sailing partner, get my own small dinghy and even get a sailing teacher license a couple of years later to be able to pass the enjoyment of that sport on to other students.

Sailing has massively impacted my life since then. In my regular profession, I’m an electrical engineer, dealing with control and protection systems for HVDC power transmission converters. When I was asked to go abroad to the UK for a whole year of commissioning as part of my first project, the decision was easily made after discovering a sailing club very close to the construction site. I just couldn’t have coped a year without sailing anymore, and so the local sailing club south of London got their first member from abroad, just one week after my emigration. The weekends down at the club enabled me to get into contact with some local people after work, I made some really close friends that I’m still visiting regularly, and I stayed a member for more than 10 years after. Without the sailing, I probably would never have returned.

I perceived Britain as a true sailing nation, with a very pragmatic approach to tackling things. After passing some German yachting licenses I still had the feeling that I wanted to learn more, to become a better sailor. Luckily, I found a friendly sailing school up in Scotland, that helped me train to pass my Yachtmaster exam with the British Royal Yachting Association, very renowned, but a challenge on its own.

Ever since a skipper from Germany persuaded me to join him on a trip on a planing racing boat, I realized my affection for the more ‘serious’ kind of trips: cold, wet, fast and windy, and with a limited crew count. Planing boats are very powerful – big sails, relatively little weight, flat hull – and very technical.

They can travel at high speeds of 20+ knots (which is just 35km/h but considered as very fast in the sailing world). This performance allows almost no interior furnishing, just bunk beds, little comfort, little privacy – yet I adore the pure technical focus on the sailing capabilities.

Racing boats are very rare to find with cabin charter opportunities. The initial transatlantic crossing I managed to reserve a space on was supposed to happen mid 2020 on a 65 feet former Volvo Ocean Racing fleet boat, which seemed like an impossible dream come true for me. But when Covid kicked in and the world came to a halt, that dream vanished quickly – and painfully.

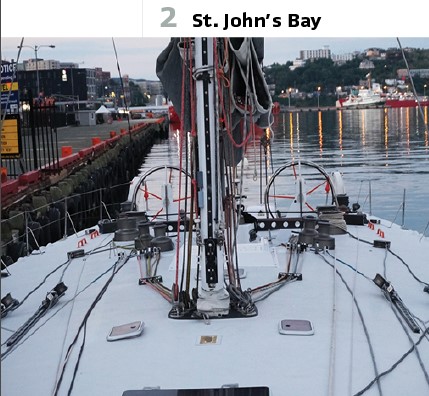

After two long years, with the skipper’s company almost hitting bankruptcy, a new opportunity to do the Atlantic East-West crossing re-appeared: a route from St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, to Southampton, UK. 2000 nautical miles to go, the shortest possible distance between the continents, estimated 12 to 14 days en route on an even bigger 80 foot so called „Maxi“racing boat. How could I say no?

So, after a one-way flight with no return ticket, I finally found myself standing in St. John‘s marina, mid-July 2022, waiting for a boat to catch. St. John’s, by the way, was the location where in 1733 the first transatlantic morse code radio transmission was received. A huge technical achievement back then – yet almost irrelevant and forgotten in modern times of high-speed internet connections, satellites and sub-sea fiber-optic cables.

The skipper arrived with bad news: due to still persistent fear of Covid some crew members had cancelled at the last minute, some were already on their way but tested positive and not allowed to enter the country. Even with an US army officer jumping in at the very last minute, the total crew including skipper was only 7, instead of typically 10-14 required for that kind of boat.

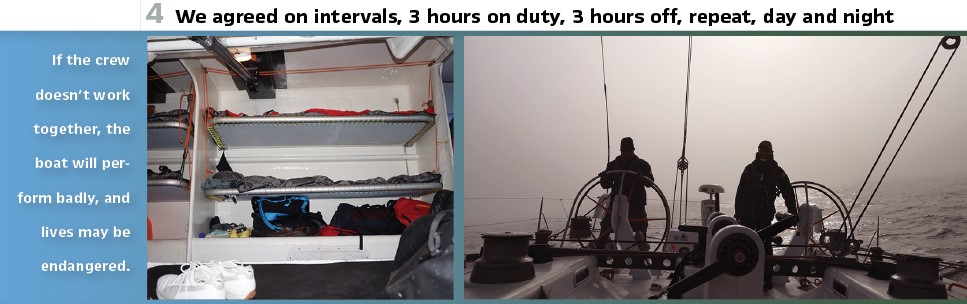

Doable, but that would mean more work for each individual crew member. If you’re not into sailing: long-distance sailing trips are run on a continuous watch scheme, similar to work shifts. You have to keep the boat running 24/7, as you cannot simply stop in the middle of the Atlantic. We agreed on 3-hour intervals, that means 3 hours on duty, 3 hours off, repeat, day and night. The people on watch keep operating the boat, do the steering, sail trim, navigation, lookout for other ships around (or even icebergs) and the people off watch either sleep or do the „household “chores, like cleaning or preparing some food. A maximum of 3 hours of sleep in a row seems hard at first, but the human body is astonishingly capable of adapting really quickly to that rhythm.

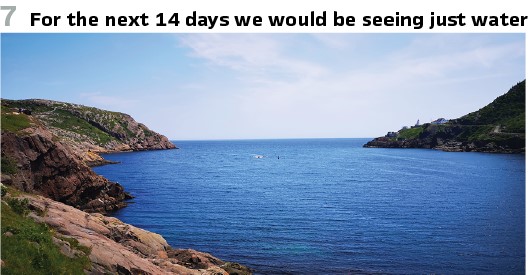

After three days staying in the marina, with compulsory technical introductions to the boat (lots of levers, ropes and winches to operate), the different sails, and the get-to-know-each other we finally set sail, passing the narrow entrance of St. John’s Bay with the Atlantic Ocean in front of us, reaching towards the horizon. For the next 14 days we would not see anything else other than water all around us, fully dependent on wind and waves and totally exposed to the weather conditions.

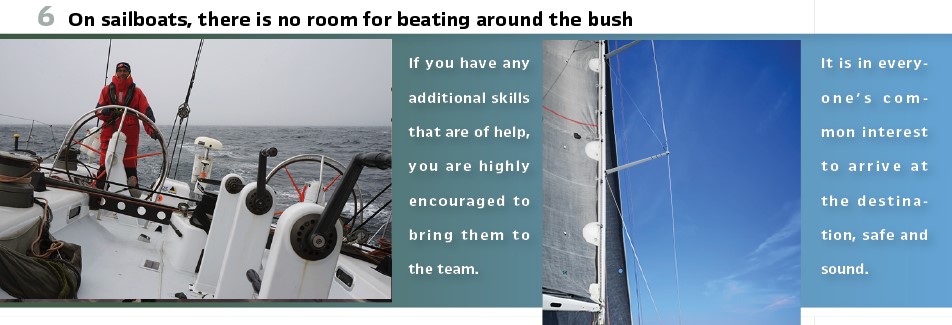

There are a few things I really adore about sailing, and this intensifies with long-distance trips. On sailboats, there is no room for beating around the bush. If you are assigned a task and accept it, you have full responsibility and have to perform. If you don’t know how to do it, you’re expected to clearly state, without being judged, and will be taught. If you’re not able to do it on your own, some other crew will naturally help you, you just need to ask. If you have any additional skills that are of help, you are highly encouraged to bring them to the team: electrical soldering skills, engine knowledge, passion for cooking, medical training – you’re highly welcome. Why? Because it is in everyone’s common interest to keep the boat running with one clear target: arrive at the destination, safe and sound.

There is no place for assumptions or false modesty. There is no time for big discussions or excuses. This may seem harsh initially but takes away a lot of stress for everyone.

If the crew doesn’t work together, the boat will perform badly, and lives may be endangered. Even the slightest moment of inattention may end in a critical situation for either crew or boat. The skipper’s task is to set the route, manage, train and orchestrate the crew, make them work together, important especially in cases of unplanned events and sleep deprivation. The goal is to have the crew create immense trust in each other, be aware of each other’s capabilities, special skills and weaknesses, within the shortest time possible.

I’ve taken part in many team building events throughout my job career, but none of them came anywhere close to the teambuilding you experience after a couple of days on a sailboat with a demanding course and a good skipper.

Decisions en route need to be made fast, and they need to be made. Not doing anything and waiting is often the worst of all options – if you don’t alter your course, you will hit the obstacle or thunderstorm. If you don’t change the sails with the wind and wait too long, you might break your mast and end up with a lot of damage, unable to maneuver. A characteristic I see gradually declining in my business environment: people, even managers, often avoid taking full responsibility and don’t dare to make decisions when there is risk involved on both sides. As a sailor, I often hear managers using phrases like “we have to set the sails,“ or “we all sit in the same boat“ – how little do they realize the true meaning behind these phrases.

What does a typical day look like when you’re crossing the Atlantic at 30 km/h? Divided into ever repeating 3-hour watches, you tend to perform a similar routine. One crew regularly checks the navigation (GPS these days, luckily), meteorological readings and weather, sets the current course to steer and writes position, course and speed into the logbook – as an analogue backup in case electronics fail. Another one operates the steering wheel, and yet another one trims the sails. In permanent rotation, as boredom leads to a lack of attention. The skipper usually stays on call in the background and has the crew operate the boat independently.

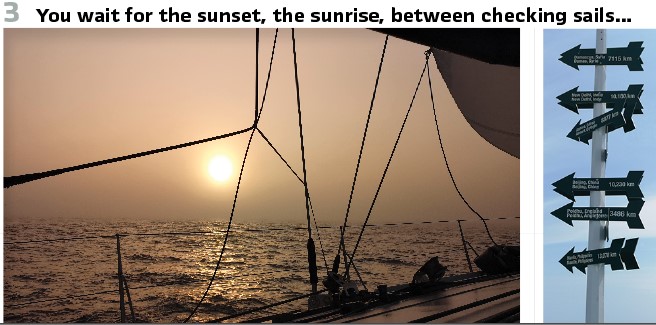

You wait for the sunset, the sunrise, in between checking sails, engine and motor, fixing all technical problems on the go (and there are always many), whilst you hope that the next watch will bring you a hot coffee or tea up on deck or prepare you a nice meal. The simplest things can be the most amazing when you’re out on the sea. No external influence at all (apart from the weather forecast via satellite and an emergency satellite phone). A lot of time for good conversations and banter. You really get to know your crewmates, and you should.

Typically, the star sky out at sea is supposed to be amazingly bright. During my trip, however, I didn’t see a single star! We started in cold fog, which almost seemed to follow us. But you can’t change it and have to cope with it, visibility of only hundreds of meters and sometimes a few miles, steering towards the horizon. Some nights sailing in complete darkness do get very long, time almost seems to stop. And the occasional storms and rain showers may frighten you at first. But once you’ve mastered steering the boat in complete darkness and huge waves, howling winds, waves that keep bashing you around, just with the compass as a guidance and always fearing to crash the sails – you gain confidence in your and the crew’s abilities and you begin to get used to this extreme situation.

Our trip took 11 days in total after departure – unable to achieve full performance level due to a limited crew, but still at a good average speed. A lot of fog, huge waves, two storms, one at night, some whales and dolphins guiding our path. On board: the Canadian skipper, very experienced and open-minded, his 16-year-old nephew on a first trip experience to Europe, a German doctor and her husband, a university professor, emigrated to Canada, a businessman from the UK and an army sergeant from the US Marine. Completely mixed ages, personalities and backgrounds, and that’s another great thing I appreciate about sailing: it constantly gets me into contact with people outside my private friends-family-work-bubble. People that I would never have met or talked to so intensively otherwise. People of different nationalities, professions, backgrounds, political or religious beliefs – with a lot of life stories to tell and personal experiences and views to share.

The feeling was amazing, when after 11 long days at sea the first vague coastline of England came into sight. A feeling of “we’ve done it,“ “we’ve managed,“ “we’re almost there.“ Mind-blowing. Following a sail in sight of the South English coast, passing the famous Needles rocks into the Solent waters, and finally the approach to Southampton Marina let us all realize that the trip was heading towards its end. Watching the skipper maneuver and dock the 80 feet sailing boat, 12 tons, into a small docking back at the marina was impressive.

We finally had arrived: 2114 nautical miles after departure, on a different continent, after crossing a complete ocean, safe and sound. And still I am just not able to imagine how our forefathers managed to do this in the old days – without GPS, satellite weather forecasts, synchronized clocks and even without correct maps.

Having packed my bags, said goodbye to skipper and crew, the adventure of a lifetime came to an end. The only thing left was to return home, go back to work, slightly tired and exhausted, but happy and in a good mood. Wondering where the sea would take me next.

Biography:

Nicolas Soellner is an electrical engineer with majors in power engineering, power electronics and communication technology. In 2008 he did his master’s degree in Erlangen, Germany and has since then been working for a manufacturer of high voltage direct current transmission converters. He is designing and testing control & protection systems for high voltage direct current transmission, used in transmission grids and for offshore connections. His work comprises functional substation operation and automation concepts, software engineering, interfacing and communication from bay throughout SCADA and network control center levels.