PAC World: When and where were you born?

D.R.: I was born in 1948 and grew up in Denison, Texas, a Railroad town north of Dallas. This was the birthplace of President Dwight Eisenhower.

PAC World: Where did you go to school?

D.R.: I attended Denison high school and graduated in 1966.

PAC World: Did you have any specific interests while in school?

D.R.: Since I was not very coordinated, my interests in high school focused on academics. I was in the debate club, participated in speech and thespian activities, and sang in choir. We formed a men’s quartet and performed for local groups. I also worked as a music director for local churches.

PAC World: Can you think of someone or something in your childhood that influenced your decision to become an engineer?

D.R.: I had excellent math, chemistry, and physics teachers in high school. It was the 1960s at the beginning of the great technical revolution in America. We were going into space and playing with things called computers. If you were good in math and science, you needed to be an engineer.

PAC World: Where did you go to university and why did you choose that particular one?

D.R: In 1965 I was selected to participate in an NSF summer engineering program at Texas A&M University. That summer convinced me I wanted to be an engineer and that I wanted to go to Texas A&M. I would note that I hadn’t fully grasped the fact that Texas A&M was still an all-male school!

PAC World: Why did you study electrical engineering?

D.R.: I had always been interested in electricity. My father taught me how to wire a house. I was fascinated by popular mechanics articles on electricity and electromagnetics in my physics courses. I decided to build my own motor. I was successful; it ran fast for a short period of time. Deciding to be an electrical engineer seem to be the natural thing to do.

PAC World: Why did you decide to continue your education to get a Ph.D. and why at a different university?

D.R: I received my BS degree at Texas A&M and was offered an NSF fellowship, so I decided to continue for a master’s degree. I worked in several internships for Texas instruments.

During my masters the department was short of teachers, and I was asked to teach a course in electric engineering for non-EE majors. That was my first introduction to university level teaching. But when I graduated, I was not sure what I wanted to do. As a Christian I had always been interested in scripture and I had worked with young people in churches, so I decided to take a break from engineering and go to Abilene Christian University to study. They gave me a job teaching physics so I could take graduate theology courses.

I had met the great love of my life, Becky Crawford, while in school at A&M. Her father taught petroleum engineering. While I was at ACU we decided to marry in 1973. Becky was still in school, and I had a wife to support.

I was offered an instructor’s position at the University of Oklahoma which allowed me to also study for a PhD. So that’s where we went.

PAC World: Is there any specific reason to choose an academic career?

D.R.: My teaching at ACU and in graduate school and my subsequent teaching at the University of Oklahoma convinced me that an academic career in teaching and research was for me.

After completion of my PhD, I joined Texas A&M University as an assistant professor.

PAC World: You spent more than fifty years teaching. Do you see any difference in the students when you started and today?

D.R.: I have now taught at the university level for 53 years. I’ve had the privilege of instructing thousands of very

intelligent young people.

You ask if the students of today are different than those when I started teaching.

I do not believe that students today are more or less intelligent than those over my entire career. It is clear that the preparation for college today is very different than when I begin teaching.

The typical student in the early 1970s that wanted to study engineering had basic math and a single physics course. But most high school graduates had never taken calculus, no one had studied computer programming, and there was no such thing as advanced placement courses.

All students started college pretty much the same in math, chemistry, physics, and Fortran programming. The student today may come in with advanced placement credits in calculus, physics, chemistry, and have programming skills.

PAC World: You have been involved in research on a wide range of topics. How do you explain your interest in so many topics and do you have a favorite?

D.R.: Very early in my career I focused on research. In the mid-1970s, the PES Relay Committee declared that high impedance faults on distribution circuits was a persistent, fundamental problem in the industry. In 1976 the Electric Power Research Institute solicited researchers to work on an effective, a practical means for detecting high impedance faults.

I had ideas on how a computer could perform continuous signal processing of sensitively sampled electrical signals on a distribution circuit and detect characteristics of downed conductors.

EPRI gave me a research contract and for several years we worked to develop pattern recognition techniques for detecting high impedance faults.

We established the Downed Conductor Test Facility of the Texas Engineering Experiment Station and conducted several years of downed conductor testing at this facility and on active utility circuits.

Our work resulted in a number of US patents. The first practical technique for High Z fault detection was commercialized by General Electric using our patents.

PAC World: You have been for many years the Chairman of the TAMU Conference for Protective Relay Engineers.

What do you think is the role of these conferences in our industry and why is it important for practicing engineers to participate in conferences?

D.R.: For over 30 years, I have served as the chair of the Texas A&M Conference for Protective Relay Engineers. I served years as meetings chair for the Power Engineering Society.

I believe technical conferences are at the core of how our industry advances.

The sharing of knowledge and real-world experiences feeds progress. If everyone stayed in their own silo our technologies would not develop as rapidly as they do.

PAC World: You have been actively involved in both IEEE and CIGRE. How do you see their role in our industry?

D.R.: Professional societies such as IEEE and CIGRE provide the venues and publications for shared learning and are indispensable elements of our industry. The working groups and study committees of these organizations focus on problems that need solution and codify standards for our industry.

Participation by your best and brightest in these groups is absolutely necessary. Some of the most important friendships and professional relationships that facilitated my career, and my research came from PES meetings.

PAC World: You have been a consultant to many utilities. What do you think are the benefits of academics working with utilities?

D.R: I personally believe that my serving is a consultant and forensic engineer for electric utility companies has been the single biggest boost in my career. Too many faculty today started teaching immediately after their advanced education and have never practiced in industry.

This can be remediated by serving as a consultant to industry and doing so is extremely important.

In my case, access to utilities on a privileged basis has provided data and information that otherwise would be unavailable.

For example, a utility would be very hesitant to talk about their “failures” but by serving as a forensic investigator for utilities you are exposed to things that would otherwise never be known. This has facilitated significantly our development of DFA technology.

PAC World: What is the greatest challenge you faced during your professional career?

D.R: The subject matter we teach today is very different than it was 50 years ago. Keeping up with modern technology over the course of the last several decades has been a challenge. But engineers are taught to independently learn and adapt.

The most significant career advice I have is not to chase fads or the “topic of day” just to secure research funding. I was privileged to work in the same general research area for all of my career and I believe this is the way to make the biggest impact on any given technical area.

PAC World: What do you consider your greatest professional achievement?

D.R: My most significant professional achievement was the formation of a highly competent research team that worked for several decades to develop sophisticated techniques for detecting and identifying incipient device failures and fault conditions on electric circuits. We instrumented over 500 circuits for up to 15 years each with high fidelity data capture devices creating the largest database of fault and failure signatures in existence, over 2500 circuits-years of events.

Using this database my colleagues Carl Benner, Jeff Wischkaemper, Karthick Manivannan and I developed what is called Distribution Fault Anticipation technology (DFA).

DFA can detect distribution circuit problems, including failing devices, days before catastrophic failure causes an outage, fire, or unsafe condition.

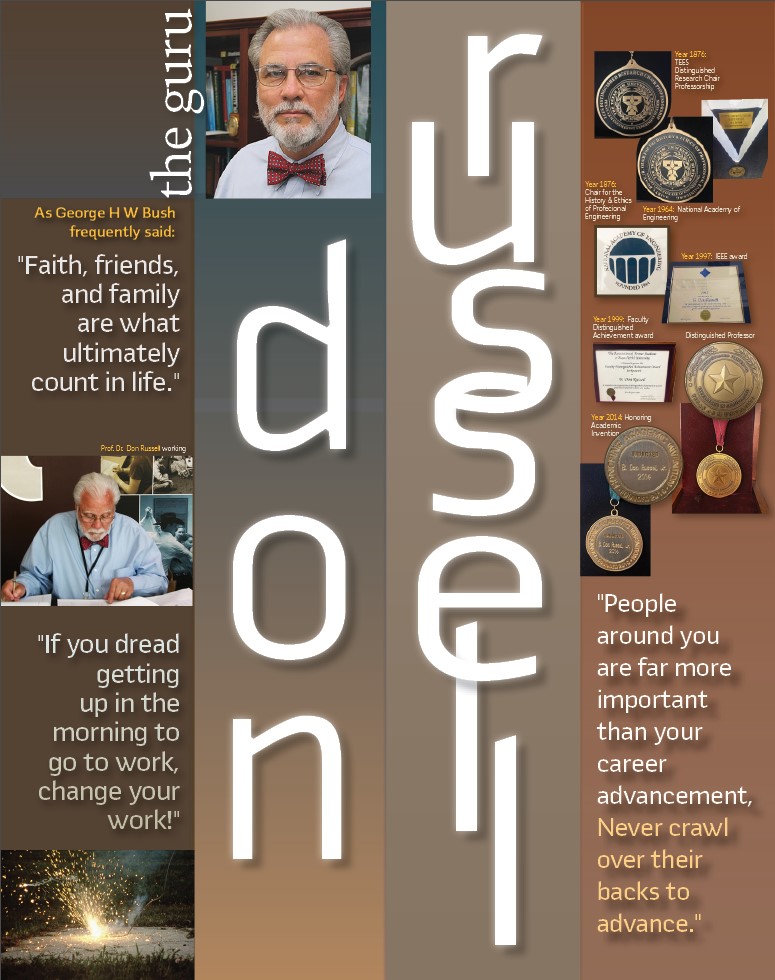

PAC World: You have received many awards. Which one do you consider the most important to you?

D.R.: Yes, I have received a number of recognitions over my career. If you stick around long enough, people give you awards!

Being elected to the National Academy of Engineering was an ultimate career validation.

However, my receipt of the IEEE Herman Halperin Transmission and Distribution Field Award and the Outstanding Engineering Achievement Award of the National Society Professional Engineers were certainly highlights.

Yes, I am a fellow five professional societies including IEEE, NSPE, The National Academy of Inventors, and The National Academy of Forensic Engineers.

PAC World: You’ve had leadership positions in many professional organizations. How do you manage all of that?

D.R: It is a great privilege to serve in leadership positions of professional organizations. My 18 years on the board of PES and my time as president were career highlights. This was at a time of great change and growth for PES and it was exciting to be involved. In recent times I have had leadership positions in CIGRE which is an organization that has a great impact on the power industry worldwide.

PAC World: Do you think it is possible to prevent wide area disturbances and blackouts?

D.R.: With respect to wide area disturbances, blackouts, and general customer outages we as engineers know that there will never be a means to fully prevent these things from happening. I’ve always taught my students, “everything made by man fails, it’s just a matter of when.”

I will leave the subject of preventing power blackouts to my colleagues who work in that area, but I think we all know that the vast majority of customer outages are caused by disruption of the distribution system. It is in that area that I have spent my career. Using advanced technologies, we can prevent many of the faults that result in outages, and we can also prevent many of the wildfires that have most recently occurred as a result of distribution circuit failures.

The distribution research area holds great promise for the use of advanced technologies to make circuits more reliable and safer. The next generation has a bright future in working to improve the electric power industry.

PAC World: You are still actively involved in IEEE and CIGRE, conferences, consulting, and innovation. What keeps you going?

D.R.: At my “advanced age” I am still very active in research and consulting. I’m still full-time at Texas A&M University after 49 years. Why stop when you are having fun!

PAC World: How do you balance your active professional life with your family life?

D.R.: It is easy for a professional career to interfere with family obligations. I didn’t do as well as I should have in my earlier years, but I have learned that nothing is more important than family.

PAC World: What do you consider your greatest personal achievement?

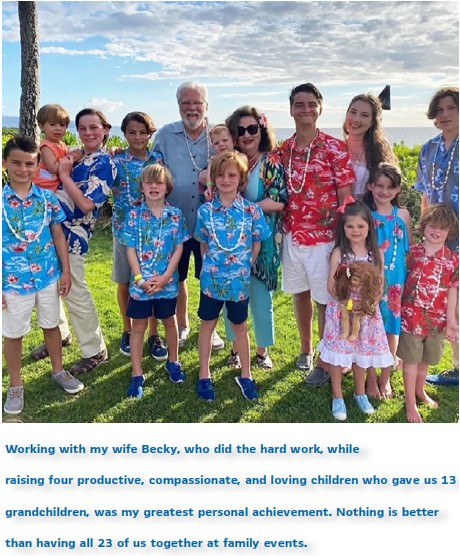

D.R.: I will say without hesitation that it was working with my wife Becky, who did the hard work, to raise four productive, compassionate, and loving children who gave us 13 grandchildren.

Nothing is better than having all 23 of us together at family events.

PAC World: What do you like to do when you are not working?

D.R.: My favorite pastime is gardening. My specialty is ferns and shade gardens. My favorite plants are caladiums

PAC World: You travel a lot all over the world. Do you have a favorite place?

D.R.: Becky and I have had the privilege of visiting over 70 countries often instigated by my professional activities, conferences, or consulting. But we always take time to see the country. My father-in-law taught me to, “go early and stay late” when you are traveling to another country.

I think our favorite places are found in Paris and rural France where we have extensively traveled. Traveling is what Becky and I think we do best as entertainment.

PAC World: Do you have favorite music?

D.R.: I may be the only engineer you know who’s first college scholarship offer was to be a music major. I decided engineering would pay better!

I do like many music forms, but no heavy metal or rap. I love Dixieland jazz, show tunes, and classical music. I was in a barbershop quartet and also sang in a group called the Studebakers which performed classic 1950s songs. It was always great fun. I also like gospel.

PAC World: What is your favorite food?

D.R.: I have a lot of favorite foods. But as an East Texas boy whose family has been in Texas for seven generations, I would probably say pork roast, fried cornbread, and turnip greens. It may not be fine dining, but it’s pretty fine for me.

PAC World: Do you have a motto? Is there anything you would like to say to the young PAC engineers around the world?

D.R.: I don’t have a specific motto. But what I believe and what I would tell young PAC engineers is the following:

Pick a career where you can get up every day and do what you love to do. That may not always pay the most, but ultimately will be the most satisfying. If you dread getting up in the morning to go to work, change your work!

The second thing I would say is this. Remember that the people around you are far more important than your career advancement. Always try to bring others up with you, never crawl over their backs to advance. Treat people with respect, compassion, and yes, love. The relationships that result will be the most satisfying thing you remember when you look back over your career.

As George H W Bush frequently said, faith, family and friends are what ultimately count in life.

Biography:

Dr. B. Don Russell is a Distinguished Professor and Regents professor at Texas A&M University where he has conducted research and taught for 49 years. He is a member of the National Academy of Engineering and a fellow of five technical societies. He holds the Bovay Endowed Chair and is the Director of the Power System Automation Laboratory of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. His research focuses on automated fault and failure diagnostics on electric power circuits to detect incipient conditions before catastrophic failure. Dr. Russell is the past president of the Power and Energy Society, past chair of the Power and Energy section of the NAE, and the former Associate Vice Chancellor of Engineering at Texas A&M University. He serves as Vice President for Administration and managing secretary for the US committee of CIGRE.