Lessons learned from IDS Deployments in Over 100 Energy Facilities

by Andreas Klien, OMICRON electronics, Austria

Ensuring the security and reliability of substations, power plants, and control centers, is paramount for the stable operation of power systems and national security. However, with the increasing integration of digital technologies and networked systems, the vulnerability of these facilities to cyber threats has escalated over the past decade. Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) have proven as a vital tool in identifying and mitigating these threats, enabling a detailed assessment of network security. We used this technology to visualize the cyber risk of PAC systems all over the world, while installing intrusion detection systems in these Operational Technology (OT) networks. This article collects our findings accumulated over the past years.

Requirement for IDS in Power Grid OT Networks

The ability to detect security incidents is an integral part of most security frameworks and guidelines, including the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, but also IEC 62443 and ISO 27k standard series. In substations, power plant control systems, and control centers, there are many devices without standard operating systems, where no endpoint detection software can be installed. Hence the detection component must be installed on the network. Hence, there are multiple national laws and regulations which require the use of IDS in critical networks, including the OT networks in PAC systems. This includes Germany, where IDS are mandatory in critical networks for more than 800 Distribution System Operators (DSOs). In Switzerland, the usage of IDS will become mandatory too in July 2024 due to a new law, which requires a higher cyber security maturity of utility OT systems. Their national regulations closely align with the NIST Cyber Security Framework. There is also high activity in other EU countries with IDS in substations, as can be observed by ongoing tenders. The latter may be related to the current geo-political situation, but also by increasing OT security awareness due to the EU NIS2 Directive, which is currently being implemented into national laws. In North America, a new NERC CIP Guideline “015 Internal Network Security Monitoring” was recently published, requiring intrusion detection measures in critical systems, including the power grid.

Intrusion Detection Systems

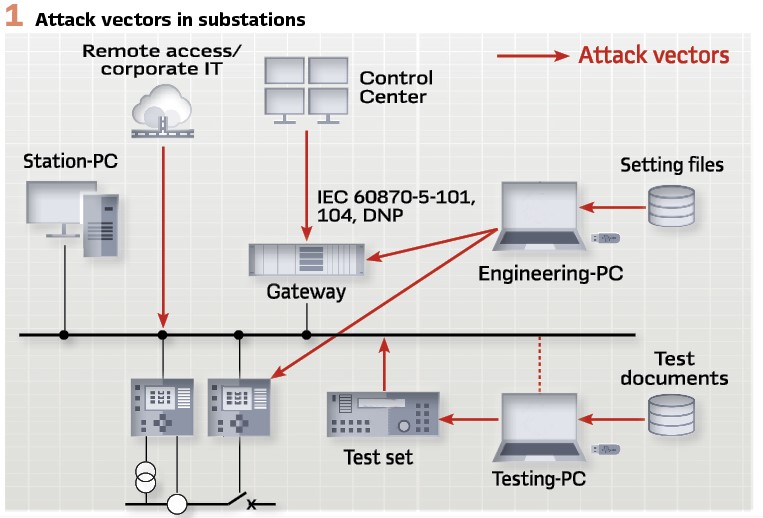

Figure 1 depicts how IDSs are used in a plant network. IDS analyze the network traffic to detect cyber-attacks, prohibited behavior, or security policy violations. There are three types of IDS available:

- Signature-based

- Anomaly-based

- Specification-based

“Signature-based” IDS scan for a list of known attack patterns and only alert if the network traffic matches one of the signatures – like a virus scanner. Signature-based IDS are thus only able to detect previously known attacks, with the disadvantage that there are only few attacks known for PAC systems. “Anomaly-based” approaches can detect yet unknown attacks, by alerting on “unusual” behavior. These systems “learn” the usual communication in the network and after the learning phase they will alert on all unusual activity.

Anomaly-based approaches are common in OT networks, because these networks are relatively stable, but they have the disadvantage of many false alarms until all activities occurred once. PAC engineers usually need to be involved to decide if a certain communication activity is a threat or normal behavior. As the learned “baseline” cannot be easily applied to other plants, every plant will have the same false alarms again, which often results in the IDS to be ignored after a few months.

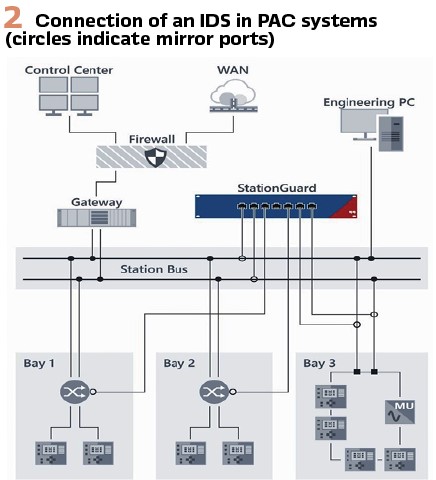

The third option for the intrusion detection approach is “specification-based”. Instead of a full learning phase where all communication must be learned, such IDS can use knowledge about the devices and the plants to set up the communication baseline (allow-list) beforehand, avoiding a long learning phase. Anomaly-based and specification-based approaches cannot be applied in IT networks, where many devices appear and disappear, as all this activity would trigger many false alerts. In OT networks in the power grid, it is however required that plugging in new devices and unknown communication triggers alerts. As depicted in Figure 2, IDS usually receive a copy of all the network traffic over mirror ports on the switches, or Ethernet Test Access Ports (TAPs).

Methodology

This article represents an experience report, where the results were collected as a side-effect after years of IDS installations, which provided the base for detailed security assessments of these plants. The findings are categorized into three main areas: technical security risks, organizational security issues, and operational/functional issues.

The first installation was done in late 2018 and since then, nearly 300 different installations and security assessments were done. The analysis in this paper thus encompasses a diverse range of energy facilities, including substations, power plants, and control centers in dozens of countries.

Most of the security and operational issues mentioned below were discovered already after the first 30 minutes after connecting to the OT network. Due to the specification-based allow-list approach, the sensor does not require a training phase. The sensor usually stayed installed for around 4-5 weeks before the final security assessment report was created. This allows to also capture seldom activity involving remote access and maintenance activities.

There are three methods of feeding a copy of all network traffic from the power plant, control center, and substation OT networks into the IDS:

- Connection to mirror ports (majority of cases)

- Connection using Network Test Access Points (TAPs)

- Collecting of data on Packet Captures (PCAPs) and analyzing them offline

The sensor was typically connected to one or more mirror ports in the OT network. In an IEC 61850 substation, an Intrusion Detection System would be connected as depicted in Figure 2 – Connection of an IDS in PAC systems (circles indicate mirror ports). Mirror ports on all relevant switches forward a copy of all network traffic to the IDS. The IDS inspects all network traffic transmitted over these switches. To be able to analyze the most important traffic between the gateway and the IEDs, the IDS should, as a minimum, be connected to the switch next to the gateway and all other critical entry points into the network. The bay-level switches don’t usually need to be covered as typically there is no communication within a bay, except multicast traffic (GOOSE, Sampled Values), which is also visible at other switches due to the multicast mechanism.

Asset Identification: Creating an asset inventory for thousands of devices is not only time-consuming, but also prone to errors. This directory must be kept up to date correctly by all technicians making changes to IEDs.

Therefore, such an equipment directory should be created automatically. For doing this, there are two options: working passively, without active communication with the system, or with an active query of the components.

Passive asset Identification: There are several advantages to the passive recording of device information in the energy sector compared to industrial automation: there are project files that describe such systems and their components in detail. For modern plants, these are not only machine-readable, but also standardized by the IEC 61850-6 standard. Security tools can read the system configuration description (SCD) files and extract information about most equipment.

The method of passively retrieving device information via sniffed network traffic is often propagated in marketing but is not very effective in practice. In normal PAC communication, type information and firmware versions are not transmitted without being queried. You would therefore have to configure another client in the system to carry out exactly these queries, which ultimately corresponds to an active querying of the devices.

Active Querying of Device Information: In many substations and power stations, the devices support the protocols in the IEC 61850 series of standards. This means that nameplates can be actively retrieved via the Manufacturing Message Specification protocol (MMS).

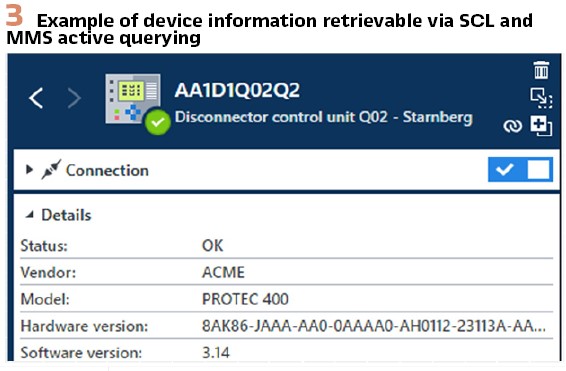

Figure 3 shows an example of which parameters can be actively retrieved via the MMS protocol and passively retrieved via IEC 61850 SCL project files: Name and description of the device, manufacturer and model specification, firmware version and in some cases also the fabrication number, or hardware version of the component.

In our solution we used when conducting the security assessments in these plants, we relied on a combination of several techniques to achieve the best possible coverage: IEC 61850 and CSV project files were imported and an optional active query via the MMS protocol was done where permitted by the operator. The IDS then automatically aggregated the information from the different sources into an asset inventory table as shown in Figure 3.

Technical Cybersecurity Issues

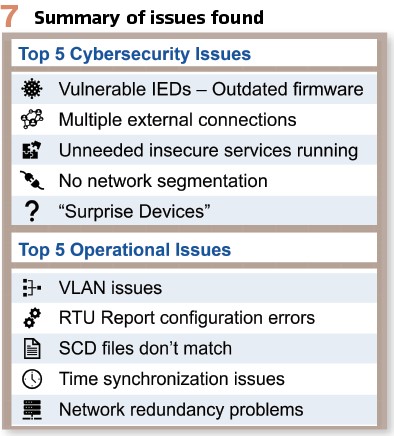

In our analysis of the different OT networks in substations, we found numerous technical cybersecurity issues. The most common of these were due to the following:

1. Vulnerable devices

2. Risky external TCP/IP connections

3. Unneeded insecure services running on the devices

4. Weak network segmentation

5. “Surprise Devices”

Subsequently, these cybersecurity issues are analyzed in more detail.

Vulnerable protection, automation, and control devices: The active asset identification StationGuard automatically detects the nameplate and firmware version of each IED in the network, enabling precise identification of the firmware versions deployed. From this, an asset inventory of the plant is created and populated into a global asset inventory list which summarizes all assets from all sensor locations.

While many power plants, substations, and control centers operate SCADA, protection, and networking equipment on older firmware, this is not inherently problematic, but the resulting risks must of course be addressed. Given the challenges of patching in power grid OT, alternative mitigation strategies are often more feasible.

The vulnerability database included in StationGuard GridOps facilitates the automatic determination of known vulnerabilities for all devices on the network. Our investigation into the vulnerabilities of these devices with years-old vulnerabilities revealed a significant accumulation of critical vulnerabilities over the years. This is compounded by additional security risks, such as the ones detailed in subsequent sections.

For instance, the CVE-2015-5374 vulnerability in protective relays, which permits a Denial-of-Service (DoS) attack through a single User Datagram Protocol (UDP) packet, causing the relay to freeze until rebooted, thus stopping all communication and protection functions. Despite the availability of a security patch since 2015, our findings indicate numerous devices still operating on pre-2015 firmware, rendering them vulnerable to this exploit, which was notably leveraged in the Industroyer 1 cyberattack on Ukraine’s power grid in 2016.

Other vulnerabilities in GOOSE implementations in protection relays can affect the communication module of these relays if specially crafted GOOSE messages are received (e.g., CVE-2023-4518, CVE-2022-1302, CVE-2022-22725).

Although MMS is transmitted on TCP/IP, the MMS protocol again brings with it all the OSI transport and flow control mechanisms which would already be provided by TCP. The large number of handshakes, each with negotiated connection parameters and window sizes, results in great complexity, which often leads to software errors and vulnerabilities. One indication of this is the large number of vulnerabilities that have been made public in connection with the port number 102, which is also used by MMS.

We advise that, while patching of PAC devices is difficult, at least mitigation steps shall be taken for the vulnerabilities known for these devices. This implies that the asset inventory must be kept up to date, including a precision which is sufficient for assessing the vulnerabilities of these IEDs.

Risky External TCP/IP Connections: In many power plants and substations, we found multiple undocumented external TCP/IP connections interfacing directly with network switches, RTUs or sometimes protection relays. The engineers who were present during the on-site visit often were not aware of some of these connections, as they were established by other departments. Grid communications departments have permanent network switch monitoring connections, the SCADA department has multiple permanent connections to the HMI and RTUs. The protection engineering department connects to retrieve disturbance records and to monitor if new disturbance records are available.

The record was a substation with over 50 external IP addresses which have a permanent connection to different devices in the substation.

Not needed insecure services running: When monitoring the network, it is possible to find services installed on PCs, which announce themselves using broadcast messages. These are the most frequently found services, which were in most cases not needed for the operation of the plant:

- Windows file sharing services (e.g., netbios) which were confirmed to be not needed on that machine

- IPv6 services of Windows, while IPv6 services are known to open a number of attack vectors

- HMI and RTUs with licensing services (e.g. “Sentinel SRM”) looking for license servers available on the network. Such services often run with elevated privileges in Windows and thus pose a risk

- PLC debugging functions (e.g. Codesys) broadcasted on the network and openly accessible

One of the common issues we found in power plant control networks is the lack of proper hardening of Windows-based devices. These devices can be easily compromised by attackers or malware and used as entry points to the network. Therefore, it is essential to apply best practices for hardening Windows devices and reduce their attack surface. One source of such best practices is the Center for Internet Security (CIS), which publishes benchmarks for various operating systems, including Windows. The CIS benchmarks provide detailed guidance on how to configure Windows settings, disable or restrict unnecessary services, apply security policies, and monitor the system for anomalies. The CIS benchmarks can be downloaded from www.cisecurity.org/cis-benchmarks and customized according to the specific needs and constraints of the power grid environment.

Weak Network Segmentation: This security issue we found to be particularly common for power plant and control center networks. Many of the power plant control networks we assessed were one big network with hundreds of devices without any network segregation.

Network segmentation is a critical security measure in plant networks for several reasons: It limits the attack surface by dividing the network into smaller, manageable segments. This way, if an attacker gains access to one segment, the breach does not necessarily compromise the entire network. To introduce segmentation into an existing OT network, first a communication analysis must be done, which we did with StationGuard. This will show which devices communicate with which other devices. This provides the base for segmenting the network along these borders.

Network segmentation is also important in substations, for example isolating the substation network from the bigger SCADA network and isolating the station bus from the management/engineering network. We have seen examples where also a group of substations were interconnected into one big multicast domain with the goal to send GOOSE between all stations. However, this also increases the attack surfaces as cyber-attacks in one station can easily propagate to the other stations – or interfere with the GOOSE subscribed in the other stations.

The worst example was one substation, where full access to the office IT network of the utility company was possible from a switch in a remote substation.

Unexpected Devices/incomplete Asset Inventory: In many plants we visited, we found more devices in the network than expected by the engineers who were present, which means that there were more devices than listed in the asset inventory of the plant. These additional devices ranged from IP cameras, printers, PCs, and even automation and control devices.

One possible reason for the discrepancy between the asset inventory and the network scan is that some devices were added or replaced without proper documentation or authorization. This poses a serious security risk, as these devices (like IP cameras) may be infected with malware. As these devices are not tracked in an asset inventory, their vulnerabilities and associated risks can also not be assessed. Furthermore, having unknown devices in the network may interfere with its performance and reliability. To prevent this problem, it is essential to have a clear and updated asset inventory, as well as a strict change management process that requires approval and verification of any modifications to the network.

StationGuard can help with this task by providing an accurate and comprehensive view of all assets in the network, as well as alerting the operators of any changes or deviations from the expected configuration.

Organizational Cybersecurity Issues

It is important to point out some organizational issues we commonly experienced in utilities operating the power plants, substations, and control center networks that we visited. The technical cybersecurity issues that we found were caused by, or augmented by these organizational issues:

1. Departmental squabbles

2. No dedicated OT security officers, IT is responsible for OT security

3. Lack of personnel

Departmental Squabbles: One of the most frequent organizational security issues we saw in many utilities is that the IT department, responsible for security and the OT department is responsible only for the operation and maintenance of the power grid. Since these two departments were far away from each other until recently, there is a lack of knowledge and understanding on both sides for the responsibilities and challenges of the other department. In many utilities there are also no social connections between people working in both departments. This causes “department thinking” and we heard both of these statements multiple times: “The IT folks won’t let us test our relays!” and “The OT people always do their own thing and completely ignore security!”. It is important to realize that securing the power grid is only possible if both departments work together. IT security experts need to understand that natural disasters and faults on power lines pose a higher operational risk to the availability of the power grid than nation-state hackers.

On the other hand, the geopolitical situation dictates that we need to protect our critical infrastructure better against cyber-attacks than we did in the past years. Our power systems are very vulnerable in this regard. The last chapter in this paper will show an example of a secondary systems architecture where cyber security and maintainability was considered in the design. The OT engineers in that utility even prefer to work in the new substations because they can use remote maintenance in the new stations. This could be a role model for collaboration between PAC engineers and security officers to achieve better resilience of the power grid.

No Dedicated OT Security Officers: The “interoperability issue” between security officers and PAC engineers described above often has an organizational root: there is no dedicated OT security officer assigned for the cyber security of the power grid. In such utilities, the Chief IT Security Officer (CISO) is responsible for OT security as well as IT security, without any staff with PAC knowledge. The protection, automation, and SCADA departments are happy that security is none of their concern, but the security measures are implemented without any knowledge about OT devices and protocols and without knowledge about the processes in OT.

We noticed that the utilities have made more progress in OT security when there was a dedicated OT security officer, working together with the CISO. This person is often somebody with a SCADA background, but a strong training in IT security and the corresponding national regulations is important. Ideally, that person has no other operational duties, except the security of the power grid OT. This ensures that the security measures chosen are in accordance with the OT engineering processes and that the OT engineers participate in the security processes.

Lack of Personnel: In many cases, cybersecurity was not considered even for new substation projects, except sometimes a firewall for perimeter defense. We got in touch with the utilities at a point where the first cybersecurity measures for substations or power plants were assessed. At control center level, cybersecurity has been a topic for longer already.

Even if cybersecurity was considered in current substation projects, there were not enough human resources available to address cybersecurity concerns in existing substations, which will only be renovated in about five years, for example. It is important to also design retrofit security measures to improve protection and detection capabilities in existing substations, until they are renovated as part of a larger project.

Some utilities planned to install an IDS in legacy substations to be at least able to detect compromises and intrusions even if they were not yet able to install state of the art protection measures like network segregation and patch management.

Conclusion

The cybersecurity of critical PAC systems in substations, power plants and control centers are increasingly at risk because the vulnerabilities and attack surfaces in OT networks are growing. Security assessments in substations and plant control networks can reveal these cybersecurity risks in their OT networks. Some of the findings can be even highly unexpected to substation engineers and IT specialists.

In this article, it was presented how an IDS – even when applied only temporarily – can support the assessment by passively monitoring the traffic in the communication network, and optionally also by querying nameplate information. The article discussed how IEC 61850 SCL configuration data can contribute to the asset inventory and vulnerability management process, and how an IDS with deep PAC protocol understanding can detect not only cyber threats but also functional issues in the OT network.

At the same time, there is a considerable need for improvement in the security processes and their governance. In addition to well-trained interdisciplinary IT/OT teams, this also requires modern tools and security architectures including monitoring and intrusion detection.

Biography:

Andreas Klien received the M.Sc. degree in Computer Engineering at the Vienna University of Technology. He joined OMICRON in 2005, working with IEC 61850 since then. Since 2018, Andreas is responsible for the Power Utility Communication business of OMICRON. His fields of experience are substation communication, SCADA, and power systems cyber security. As a member of the WG10 in TC57 of the IEC he is participating in the development of the IEC 61850 standard series.