By Rene Troost, Stedin, The Netherlands

As a small kid, I was really impressed by the organ and the capabilities of some organists.

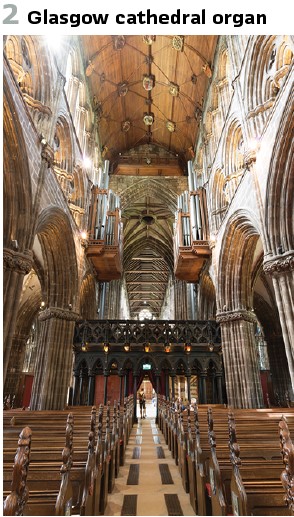

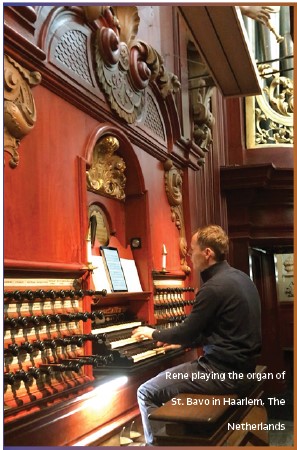

It was back in 2015, when the PAC World conference was held at the Strathclyde University in Glasgow. On the last day, the excursion leads us to the Power Network Demonstration Center (PNDC) of the Strathclyde University. We arrived slightly earlier in Glasgow after the excursion, which gave me some spare time before flying back home. Passing by the Glasgow Cathedral, I asked the driver to let me get out, to say goodbye to all the technical tour attendees. Alex asked me: “What are you going to do?”, “Playing the organ” (Figure 2) was my answer. Looking at his face was really humoristic, Alex totally didn’t expect that answer and was not aware of my hobby.

How did I start? I always go to church on Sunday. As a small kid, I was really impressed by the organ and the capabilities of some organists. It was not a question when to start organ lessons: as soon as possible. However, I more or less stopped playing the organ from my 13th year of age. I needed all my time to discover another passion: electronics. It was a big pleasure to fix defective tape recorders, computers, monitors, and everything with a cord… Every day I was figuring out how things are working, by disassembling and (trying to) reassemble it.

From the age of 16, me and my older brother, who already owned a car, started to discover organs in The Netherlands. From that moment, my passion for the organ was alive again. The incredible machines and majestic sounds still impress me.

What is an organ? Everyone knows a flute, a trumpet or clarinet. On an organ it is possible to play all these sounds together. Where these separate instruments have one instrument for a tonal range, an organ has separate pipes for every tone. An organ produces its sound by driving an airflow through pipes, activated by pressing a key on a keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single pitch, the pipes are provided in set, which we call stops. The flute is an example of a stop. Each stop has a specific timbre, volume and pitch. All stops together makes a smaller or bigger organ. If we ‘pull out all the stops’, a majestic sound will appear when playing the organ.

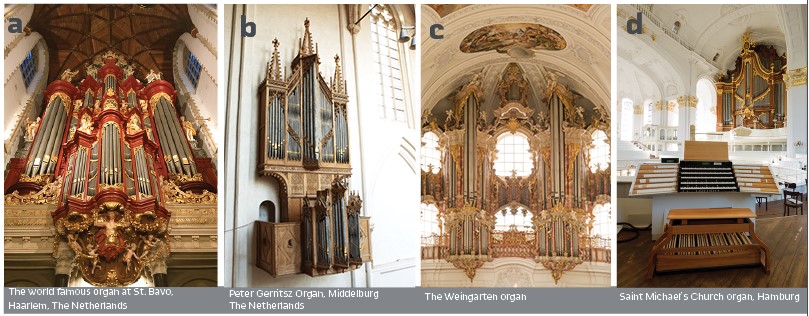

A bit of history: The history of the organ goes back about 2.000 years, with very small examples played in the Roman Empire. The real development of the organs was made in the 14th and 15th centuries. Big cities placed organs in their church buildings, mainly to use that instrument during the week, not during services. Specific to The Netherlands, most of the big organs were also owned by the government, while the churches itself were owned by the church. Still some nice, more or less unaltered examples of organs from that period exist, e.g., the Peter Gerritsz Organ (date from 1479) in the Koorkerk, Middelburg, The Netherlands (Figure b). This organ typically shows the renaissance period in its style.

Within the baroque time period, organ building came to a top-production point. Builders like Arp Schnitger (1648-1719) and Gottfried Silbermann (1683-1753) built phenomenal instruments with new possibilities, using often existing pipework and extended or renewed the organ cases. These new instruments inspired famous composers like Johann Sebastian Bach.

In 1811, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll was born to be the most influencing French organ builders in the romantic style period. He designed the organ in a way that the organist is able to generate a fast crescendo and diminuendo with very ingenious mechanic techniques.

How does an organ work? The basic principles of an organ are quite simple. By pressing a key on the keyboard, air will flow through the pipe and produce a sound. Different rows of pipes can be activated to produce different sounds separately or together. A wind supply with a blower unit and air reservoir secures a stable sound.

All these mechanics for multiple centuries have been made of only natural materials like wood, leather, metal and natural glues. The complexity comes in when the design has to operate fluently within multiple different conditions like high humidity, extreme low temperatures, etc.

A small organ with one keyboard normally has a quite short distance between the keyboard and the pipes, but within bigger organs, a distance of 10 to 20 meters can be easily met. For example, the majestic organ in Weingarten (Bayern, Germany, Figure c), where the console (Figure 3) to operate the machine is in the middle of the organ, contains an extremely complex mechanical part. Some nice details about that specific organ: it took 13 years building time, has full-ivory stop knobs and is the first organ with ‘remote controlled’ parts. I played that organ in 2016.

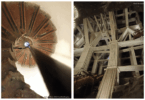

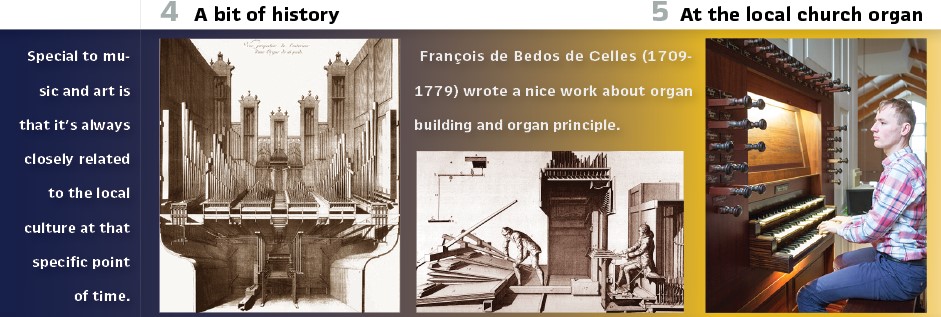

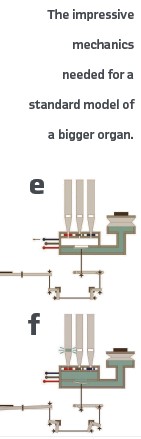

Back to the stops: An organ contains longer and shorter pipes. A short pipe of course produces a high tone, a long pipe a low tone. Using an 8 foot stop means that the longest pipe (lower C) of that stop is 8 feet long and the pitch is equal of a human voice or a piano. An octave higher can be produced by shortening the pipe to 4 feet. An octave lower can be reached by doubling the pipe length: 16 feet for the longest pipe. François de BEDOS de CELLES (1709-1779) wrote a nice work about organ building, thanks to him we have great drawings like Figures 4, where you can see the impressive mechanics needed for a ‘standard’ model of a bigger organ.

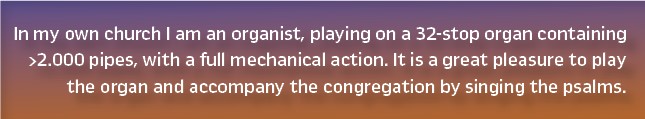

Me as an organist: In my own church I am the organist, playing on a 32-stop organ containing >2.000 pipes, with a full mechanical action. It is a great pleasure to play the organ and accompany the congregation by singing the psalms. During the services around thousand people are in the church, what results in a massive sound of a full organ and all people singing the glory of God. It always impresses me.

GOOSE organ? In more and more places, the mechanical action of the organ is being expanded with an electric control possibility. As we use fast relays to perform a trip in a couple of milliseconds, in organs solenoids are being used to trigger a mechanical action.

This trigger is initiated by a remotely placed console, connected by a fiber optic cable. This technique is very similar to what we know as layer 2 GOOSE messages. It has to be extremely fast and reliable. An example of this kind of organ is the organ in the Saint Michael’s Church in Hamburg, Germany (Figure d).

Brownfield projects: A good organ exceeds easily the lifetime of a substation, even of the primary components. In The Netherlands, thousands of organs are historic and (100 – 400 years old) and nearby all of them are in perfect condition, thanks to the great building quality and craftmanship to maintain them. Newer organs, with an electric action, have more problems. The electronic components last only for about 40 years, like our old RTU based substation automation systems. Thus, brownfield projects come up also for organ builders. That kind of projects are quite similar: no-one knows how the old stuff works and it is taking a lot of time to perform such a brownfield project.

Discovering new instruments: Special to music and art is that it’s always closely related to the local culture at that specific point of time. On a regular base, my friends and I are travelling to discover new instruments and cultures. Organs from the 16th century in Italy are totally different from the instruments built in France.

The same applies for instruments from the UK, Netherlands and the USA. While the instruments from Italy are very temperamental with a lot of overtones, the British instruments are much softer and rounder of sound. Still the difference is huge.

It is more or less impossible to play old French music on a Dutch organ, or the other way around. With worldwide certainly much more that 100.000 organs, there is enough to discover.

Organists are very friendly people with great hospitality. As an organist, I have the privilege to visit places where regular tourists aren’t able to go. For example, in the roof space of the church or even joining the monks during the dinner in an Abbey…

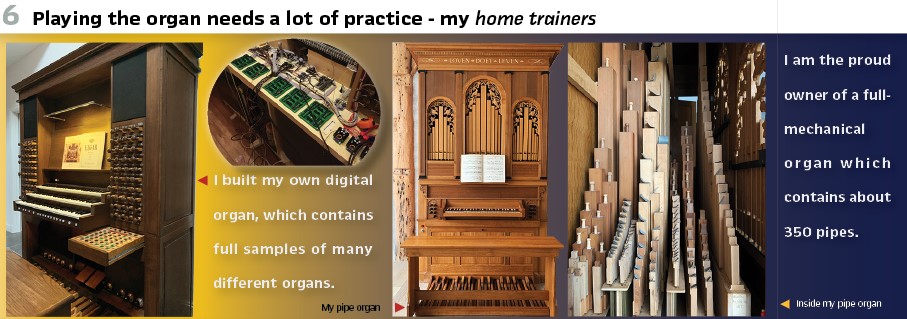

Home-made organ: Playing the organ needs a lot of practice. You need to use both hands, both feet and brain. To study, many organists have a so-called home trainer: an electric organ, imitating organ sounds. Some have a (small) real pipe organ at home. I am a lucky one to have both at home. I am the proud owner of a full-mechanical organ which contains about 350 pipes. That organ was built by the Dutch organ builder Gerrit Klop.

Separate of that, I built my own digital organ, which contains full samples of many different organs. Nowadays, there are sample sets of hundreds of different organs available. The principle is as follows: all keys and knobs are connected to multiple MIDI controllers.

The MIDI signals are interpreted by a high-specification computer to generate the requested sound. This all depends on the activated different stops. The sound shall be generated in a couple of milliseconds, otherwise the delay is too big to have a realistic interaction.

All draw stops (80 in total) can of course be pulled out or pushed in. The specialty is that all these knobs are being equipped with double solenoids, to be able to be automatically controlled. This is needed by playing more symphonic works with a lot of different registrations. Before playing the piece, I program all the different combinations and store them. With my thumb or foot, I select the next preset and the knobs are immediately set in the right position. The solenoid controllers are designed by me, including the coding of the microcontrollers.

With this kind of sampled ‘home trainer’ it is actually possible to virtually enjoy organs from all over the world. Digital is never as good as a real pipe organ, but as a home trainer, it satisfies the requirements…

Special occasions: Like birders have birds they must see; I have organs I would like to have played. Some of the largest organs I played were the massive organ in the Milan Cathedral, with 15.800 pipes, the Mormon Tabernacle organ with 11.600 pipes and the Liverpool Cathedral containing 10.000 pipes. To be honest: the biggest instruments are not always the most magnificent. Small instruments, build with great craftsmanship in a nice space can often give me more joy. In 2017, I went to Vladivostok as an IEC Young Professional and had the opportunity to give a concert on the only pipe organ there. Organ concerts are quite rare in Vladivostok. That resulted in an amount of 600 visitors, while the church was only capable of hosting 300 people…

Biography:

Rene Troost (rene.troost@stedin.net), graduated as an Electrical Engineer, and started his career in Telecommunications. In 2014, Troost joined Stedin, the DSO for the South-West area of The Netherlands, including the Port of Rotterdam. Troost is currently responsible for substation automation policy in Stedin. He chairs the Dutch technical working group designing a DSO/TSO-DER interface, is an active member of the Dutch Committee of the IEC TC57 (NEC57) and the Technical Committee TC57 WG10 that deals with power system intelligent electronic devices (IEDs), communication and associated data models and chairs the Dutch CIGRE B5 study committee.