By Brant Heap and Anthony Sivesind, Salt River Project, USA, and Marco Nunes, ABB Switzerland

Introduction – Evolution of Line Differential Schemes: Line differential protection has evolved from simple pilot-wire schemes relying on copper conductors to sophisticated widearea solutions based on highspeed fiber optics and Ethernet processbus networks. The basic principle-comparing realtime currents measured at both ends of the protected element-has endured for more than a century. Nevertheless, each technological leap has extended the possible line length, increased security, and reduced overall trip time.

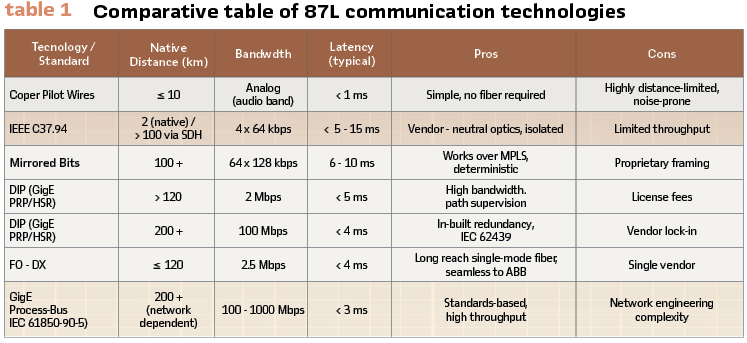

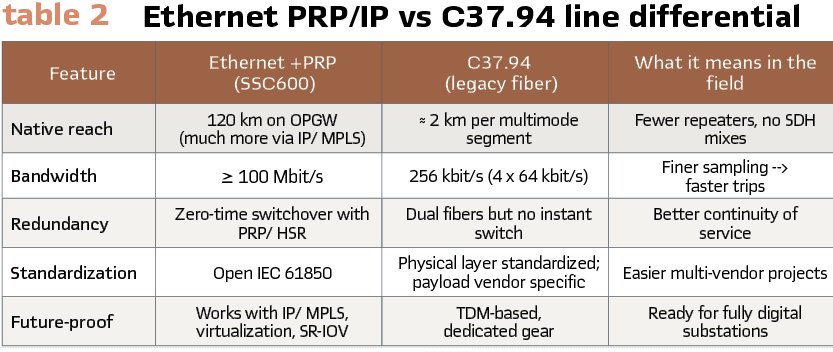

Today, utilities face highly meshed grids, multivendor interoperability requirements, and growing cybersecurity mandates. This chapter situates ABB Electrification’s SSC600 v1.5 within that landscape. We begin by contrasting the most common physical interfaces and communication profiles used for 87L schemes. (Table 1).

Traditional Copper Pilot Wires: Early 20thcentury differential relays utilized dedicated copper pilot wires. While inexpensive and conceptually straightforward, their susceptibility to induced voltages from parallel power conductors and practical range of roughly 10 km soon became a major drawback. Pilotwire maintenance costs and lightningrelated outages propelled the industry toward carrierbased and optical alternatives as transmission voltages escalated.

IEEE C37.94 Multimode Fiber Standard: IEEE C37.94, released in 2002, responded to the need for a costeffective, shorthaul (< 2 km) optical link carrying teleprotection traffic. Wrapping N×64kbps payloads onto LEDdriven multimode fiber allowed utilities to reuse legacy T1 multiplexers and maintain deterministic timing.

However, the fourDS0 upper bound translates to roughly 128 kbps net-a hard limit for modern 87L algorithms that prefer >500 samples/s per phase.

Proprietary WideArea Solutions: Recognizing the bandwidth constraint, relay vendors engineered proprietary stacks. SEL’s MIRRORED BITS® packs singlebit status and sampled analog values into a custom encoding that can ride existing synchronous SONET/SDH channels. GE’s DLAN+ leverages fullrate G.703 (E1/T1) at 2 Mbps, embedding maintenance frames for BER measurement and froginapan latency alarms. Siemens adopted Gigabit Ethernet combined with PRP/HSR, creating a routable, redundant channel dubbed Differential IP (DIP). Each solution raises underlying bandwidth to at least 2 Mbps, enabling subcycle trip logic but at the cost of vendor lockin.

Positioning of Virtualized Protection: Virtualized Protection (VPAC) functions as a Centralized Protection & Control (CPC) device. Unlike bayoriented IEDs that house one physical differential pair, the VPAC/CPC technology hosts up to six independent line differential channels in software. Users can select one of three physical interfaces—C37.94, Gigabit Ethernet, or ABB FODX—for each protected line. Automatic switchover logic maintains security; a realtime counter vetting roundtrip delay ensures that any channel break elevates the scheme into a restrained mode within 4 ms, matching ENTSOE stability mandates and best practices for high-speed protection across the industry.

Physical & Logical Architecture of CPC: The CPC is a centralized platform mounted in the control room rather than the switchyard. Its quadcore CPU runs a realtime Linux derivative, isolating protective tasks from HMI and engineering services. Redundant processbus NICs collect sampled values at 4×64 samples/cycle, while a dedicated TMS320C674x DSP executes 87L algorithms in deterministic, lowlatency pipelines.

Data Acquisition & Time Synchronization

IEEE 1588 Precision Time Protocol (PTP): The CPC contains a hardware-assisted PTP engine that supports both ordinary-clock and grand-master clock (GMC) roles:

Profiles:

- IEC 61850-9-3 power-utility profile (Class C, 1 pps + PTP) – default

- IEEE C37.238-2017 (Power Profile) – optional for North-American deployments

- Telecom Boundary Time (ITU-T G.8275.2) – for public telecom networks with partial timing support

Grand-master Mode:

- Uses the on-board u-blox F9 multi-GNSS receiver (GPS + Galileo + BeiDou) with SAW-filtered antenna input (-160 dBm sensitivity)

- Automatically switches to Best Master Clock Algorithm (BMCA) priority 1 when GNSS is healthy; priority 2 is reserved for external PTP GMCs so that station redundancy schemes always prefer a satellite-disciplined source

Subordinate Mode:

- Operates as an ordinary clock with < 80 ns one-way latency budget from master to SSC600 application layer (measured over PRP/HSR redundant LAN)

- Accepts boundary-clock chains up to four hops deep provided the cumulative asymmetry error is < 500 ns.

- Time Stamping:

- PTP event messages are time-stamped in hardware on the MAC layer, bypassing the main CPU scheduling jitter

The protection algorithm receives phasor windows that are aligned to the next 4 µs tick, yielding a worst-case phasor error of 0.11 mrad at 50 Hz (negligible for the 20 mrad security margin of the differential comparator).

Engineering Best Practices: Use GPS-referenced PTP grand masters at both line terminals whenever a telecom backbone is available; configure SSC600s as ordinary clocks to simplify firmware maintenance.

Segment protection traffic (SV, GOOSE, 87L UDP) onto a dedicated PRP or HSR VLAN; LLDP TLVs should not share the same VLAN because heavy LLDP bursts can introduce asymmetry. Validate asymmetry after fiber repairs: a 1 km Δ-length between LAN-A and LAN-B fibers equates to ~5 µs propagation skew – update the Delay Asymmetry Compensation parameters in boundary clocks accordingly.

Enable PTP autonomous locking with a re-sync threshold of 100 ns; this prevents frequent PI controller hunting while maintaining < 1 µs average offset. Log hold-over metrics via IEC 61850 DataSet “TIME-DIAG” every 15 min; if freqDrift exceeds 30 ppb / h, schedule OCXO replacement at next outage.

Inter-operability Tests: Testresults show that the CPC accepts path-delay asymmetry up to 2 µs without spurious 87L trips. A 48 h hold-over soak on a temperature-cycle chamber (-5 °C ↔ +45 °C) produced a maximum internal-fault operating time increase of 0.3 ms-still below the 10 ms ENTSO-E requirement.

These synchronization capabilities ensure that the CPC maintains deterministic, secure differential protection from remote rural substations to fully digital IEC 61850 process-bus installations-regardless of GNSS availability.

Communication Stack & Channel Redundancy

Each 87L payload is encapsulated into 24byte UDP/IP frames transmitted every millisecond. Sequence numbers and CRC32 guard against misorder and corruption. In dualport deployments the CPC implements hitless switchover (<4 ms) between PRP A/B paths.

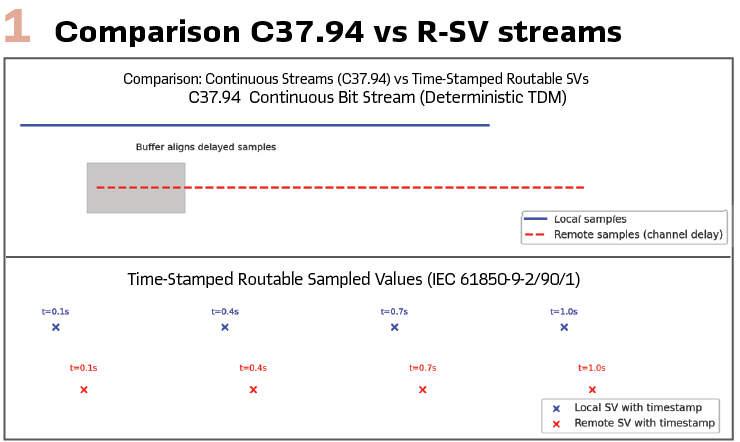

Sampled Values Communication: C37.94 vs IEC 61850-9-2/90-1: Line differential protection schemes rely on accurate alignment of current and voltage samples between line ends. Traditionally, C37.94 continuous bit streams provide deterministic transport using time-division multiplexing (TDM). Local and remote streams are continuously aligned, with small buffers compensating for fixed channel delays, ensuring synchronous comparison of samples. By contrast, IEC 61850-9-2/90-1 routable sampled values embed time stamps within each message. This approach allows samples from different line ends to be aligned based on their time tags, regardless of varying network delays. Instead of a continuous bit stream, discrete, time-stamped packets are compared at defined instants (e.g., t=0.1s, 0.4s, 0.7s, 1.0s). This removes strict dependence on channel determinism and supports modern packet-switched networks.

In practice, C37.94 offers low and predictable latency but is limited to dedicated channels, while IEC 61850 routable SVs provide greater flexibility and scalability, enabling protection functions across wide-area, IP-based networks. Both approaches can achieve the synchronization required for high-speed line differential protection, but with distinct trade-offs in infrastructure and deployment scope. (Figure 1).

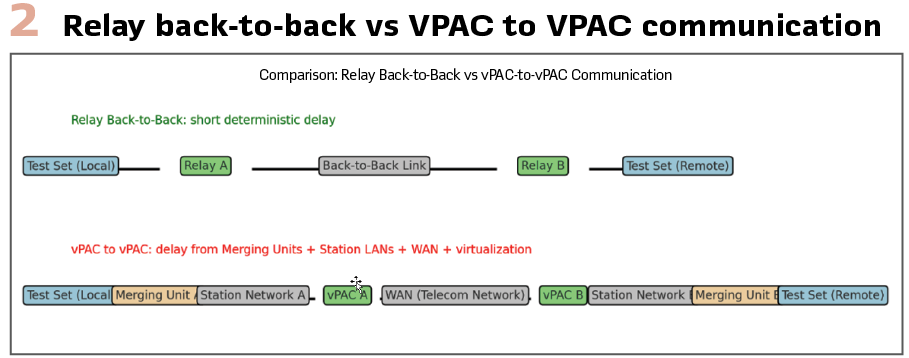

Comparison: Relay Back-to-Back vs vPAC-to-vPAC Communication: Traditional relay back-to-back testing involves two physical relays directly interconnected, with only a short and deterministic propagation delay across the back-to-back link. This setup provides a simple, controlled environment to validate line differential schemes with minimal latency.

In contrast, virtualized protection and control (vPAC) introduces additional communication and processing stages. Sampled values from merging units traverse station LANs, wide-area networks (WANs), and the virtualization layer before reaching the remote vPAC instance. Each stage-merging units, network transport, telecom backbone, and virtualization-contributes to end-to-end latency and jitter.

While back-to-back relay testing demonstrates the intrinsic speed of the protection algorithm, vPAC-to-vPAC communication reflects a more realistic deployment scenario, where networked architectures and virtualization overhead must be accounted for.

This distinction is critical when assessing the applicability of digital substations and cloud-based protection functions to meet stringent line differential protection requirements. (Figure 2).

PRP Network Interface Cards (NICs): Parallel Redundancy Protocol (PRP), defined in IEC 624393, guarantees zero packetloss recovery by duplicating each Ethernet frame across two independent LANs. The CPC can be fitted with external PRP expansion cards or utilize builtin Intel® i210/i225LM chipsets when deployed inside a virtualized CPC server.

- Hardware formfactor: dualSFP 100/1000BASESXLX with hardware PTP timestamping

- MAC address scheme: identical Logical MAC (LMAC) per frame; unique Physical MAC (PMAC) per port

- Sequencing: 16bit LAN A/B trailer compliant with IEC 624393 Clause 5

- Wirespeed performance: lossfree frame forwarding from 64 to 1518 bytes at 100 % load on both LANs

- Interoperability: validated with Hirschmann RSP35, Ruggedcom RSG2488

- Field result: endtoend latency < 3 ms maintained during fiber break on LAN A (automatic hitless failover)

When installed in a substation bay, the PRP card carries Sampled Values (SV) and GOOSE traffic in a dedicated processbus VLAN while the 87L teleprotection frames ride a service VLAN. Because duplicate frames traverse distinct paths, the first frame to reach the application layer is accepted, ensuring deterministic response even under single point failures.

Single Root I/O Virtualization (SRIOV) for CPC Servers: Utilities increasingly deploy CPC as a virtual appliance hosted on industrial servers. To avoid the latency overhead of hypervisors, NICs such as Intel® X710 or Mellanox® ConnectX4 Lx support Single Root I/O Virtualization (SRIOV). SRIOV slices the physical adapter into Virtual Functions (VF) that are passed directly to the guest OS via PCIe, bypassing the hypervisor switching layer.

- Supported hypervisors: VMware ESXi 8.x, KVM (kernel 6.6+ vfiopci)

- Processbus isolation: each VF is assigned a dedicated SV/GOOSE VLAN; 87L frames map to VF queue 0

- Latency figures: ingress 2.7 µs + egress 3.2 µs (RFC 2544), well below the 50 µs DSP window

- CPU offload: VF RSS and interrupt steering reduce hostCPU utilization by ~38 % at 100 Mbps SV load

- Coexistence with PRP: SRIOV VFs can be PRPaware when firmware supports double transmission

Combining PRP at the network layer with SRIOV inside the virtualization stack allows a centralized protection architecture to achieve subcycle clearing times without relying on vendorspecific hardware relays in each bay.

Differential Protection and algorithm on VPAC

The Journey of a Differential Packet: Every millisecond the CPC wraps its latest current readings into a small Ethernet frame. To make sure the data is never lost, it sends two identical copies:

- One on the “red” network

- One on the “black” network

This duplication is called PRP (Parallel Redundancy Protocol.)

Whichever copy reaches the far end first is used; the duplicate is discarded. Even if a fiber or switch fails, protection continues with zero interruption.

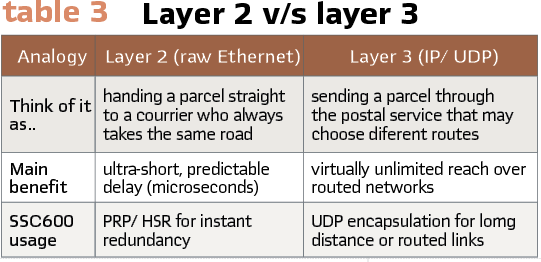

Layer 2 vs Layer 3 – Why does it matter? In practice, SSC600 first relies on Layer 2 for speed, then adds a UDP envelope (Layer 3) only when the connection stretches beyond a simple LAN.

Ethernet + PRP vs IEEE C37.945.4 A Quick Look at the Single – Line Diagram: The SSC600 manual shows a single-line diagram where each breaker changes color when it receives a trip command.

When the differential function detects an internal fault, the affected breakers turn red and open almost instantly. (See Figure 1 in the documentation.)

Step-by-Step Summary:

1. Measure – Each line end samples current 80 times per cycle

2. Time-stamp – A GPS/PTP clock tags the data with ±1 µs accuracy

3. Duplicate & send – Two identical frames leave on the red and black networks

4. Compare – The remote end subtracts its own current from the received value; if the difference is large, the fault lies between the two substations

5. Act – Breakers open within a single electrical cycle

(≈ 20 ms at 50 Hz)

In short, high-speed Ethernet, PRP duplication, and precise time synchronization let the SSC600 protect lines quickly and reliably while fitting seamlessly into modern digital-substation networks.

Testing, Commissioning & Maintenance

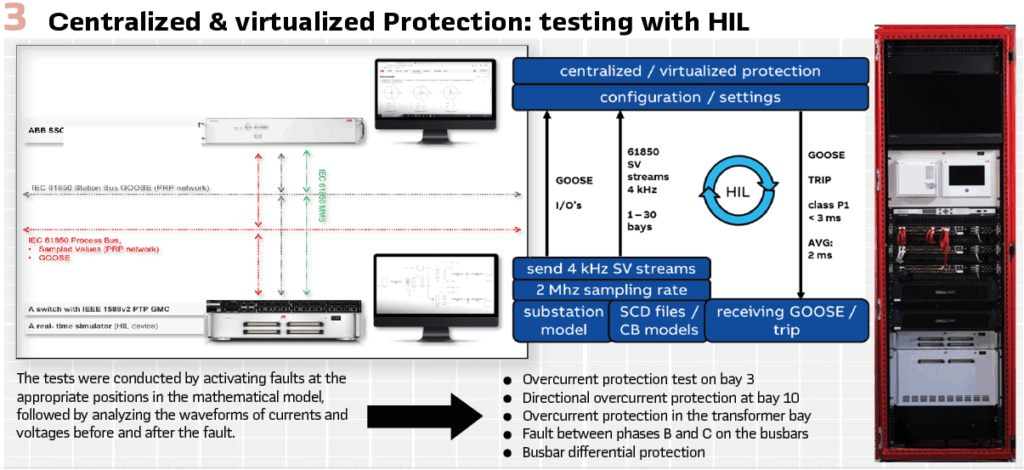

Virtual commissioning with realtime simulators is supported via IEC 6185092LE or 61869-9 sampled values replay. Field maintenance utilities allow online injection of test sets without disabling the scheme. The complete substation can be tested in during the engineering phase and on site with a mobile RTDS/Typhoon HIL kit. (see Figure 3).

Performance Evaluation & Case Studies

Salt River Project Accelerated Stress Testing and Field Implementation: Salt River Project (SRP) has deployed both a laboratory and a field pilot to evaluate the performance of the ABB SSC600-based line differential (87L) protection function. The local protection system is built on a virtualized Protection and Control (vPAC) architecture, where the SSC600 software operates as a virtual machine hosted individually on a pair of redundant, substation-hardened physical servers. The virtual machines are then managed by a hypervisor, which enables flexible deployment, resource isolation, and centralized management of the ABB SSC600. The remote terminal for the 87L protection function was implemented using ABBs dedicated SSC600 Centralized Protection and Control (CPC) hardware platform. Both the vPAC and CPC systems are interfaced with merging units via network switches, allowing the exchange of sampled values and GOOSE messages essential for protection operations.

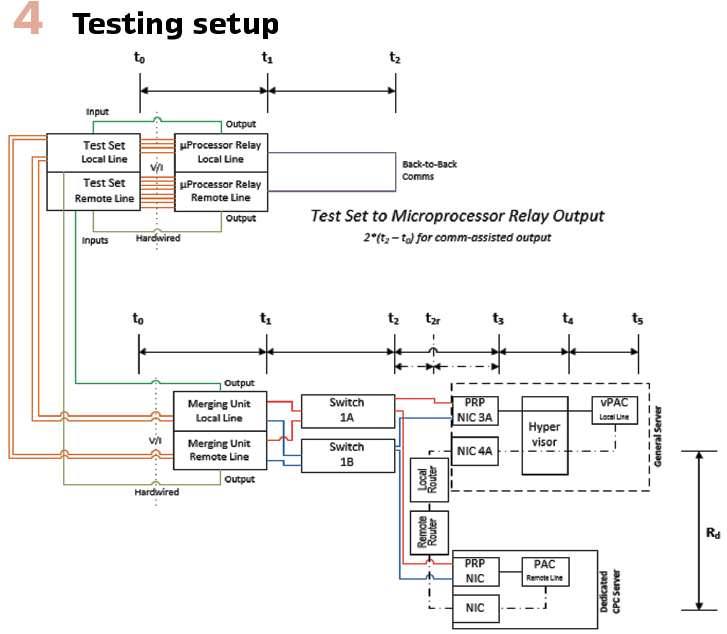

SRP developed a comprehensive test setup that enabled simultaneous evaluation of the vPAC/CPC system and a legacy microprocessor-based line differential scheme in order to benchmark performance. The legacy system uses traditional relays communicating over proprietary Layer 2 Ethernet protocols. Current and voltage signals were simultaneously injected into both systems using synchronized test sets, allowing for a direct comparison of round-trip protection response times under identical fault conditions. This architecture is illustrated in Figure 4.

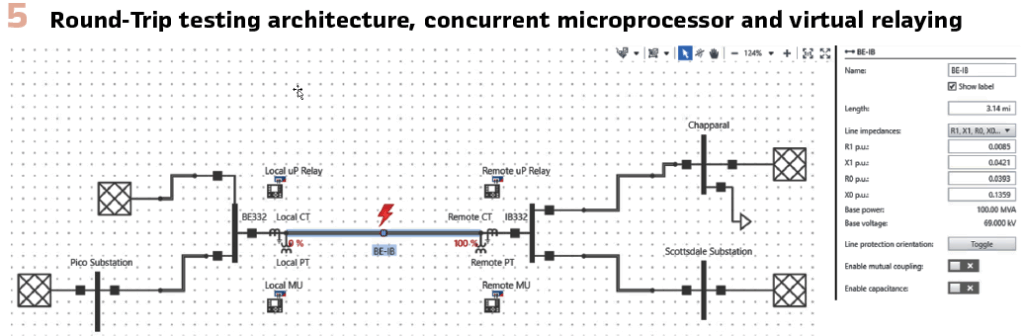

Test Setup and Configuration: The test system is configured using a test simulation environment to emulate the line differential protection scheme between local and remote substations, mimicking the field pilot conditions. The modeled line section (LOC-REM) is 3.14 miles in length, with defined positive- and zero-sequence impedances (R1, X1, R0, X0) referenced to a 100 MVA base and 69 kV base voltage.

At each end of the line, local and remote protection relays (µP Relays) are connected through merging units (MUs) and instrument transformers (CTs and PTs). These provide sampled values to the relays, enabling the exchange of differential current information across the simulated channel.

The configuration allows for flexible testing of line differential schemes under varying network conditions, including channel delays and virtualization. With Omicron, fault conditions can be injected, and the response of both local and remote relays can be observed, validating interoperability and timing performance of different communication methods (e.g., back-to-back relay links vs. vPAC-to-vPAC over WAN).

This setup provides a realistic laboratory environment to benchmark new architectures for digital substations, ensuring protection reliability while transitioning from conventional relays to virtualized protection functions.

Grid-based testing software was used to simulate line faults at multiple locations between substation terminals, while also varying fault phasing, resistance, and inception angle. See Figure 6.

This configuration of test sets provided hard-wired signals for both the local and remote microprocessor relays, as well as for the merging units (publishing SV at 4.8 kHz and receiving commands from vPAC via GOOSE messaging). Final tripping outputs were connected directly from both device types into the test sets to measure round-trip timing

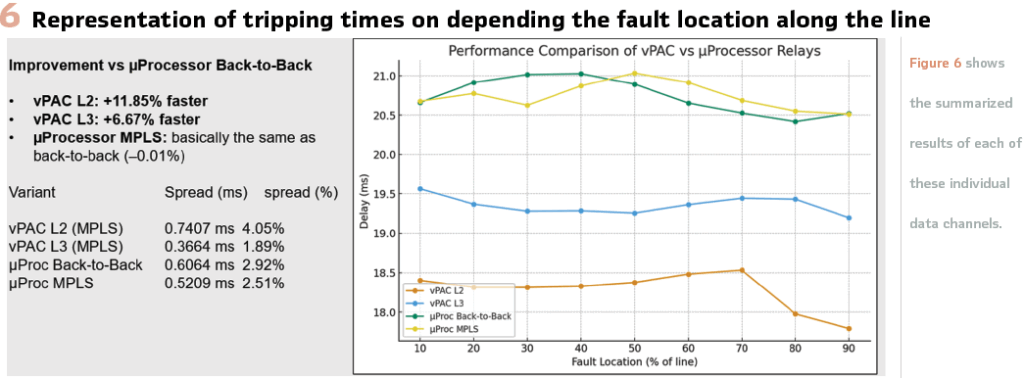

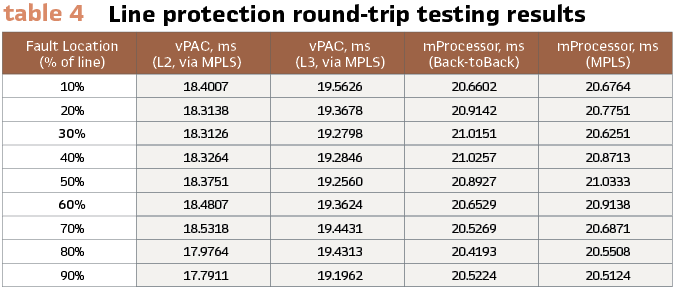

87L communications were varied in both the microprocessor and vPAC/CPC topologies. The former was tested while tethered back-to-back (as seen in Figure 4), and with MPLS routing via Virtual Private LAN Service (VPLS). The vPAC/CPC schemes were tested with Layer 2 SVs being delivered directly to both local and remote relaying via MPLS VPLS, as well as with Layer 3 SVs exchanged between vPAC and PAC relays via MPLS VPN to deliver their respective local measurements. The summarized results of each of these individual data channels can be seen in Figure 6. These results are provided in milliseconds, representing the mean of 500 iterations of varying fault types at each given fault location.

Despite the advantage provided to the microprocessor relays in the back-to-back scenario, vPAC was quicker in every case, on average, while providing consistent results. Variance between maximum and minimum times remained under 30%, which was also less than the microprocessor devices.

The variance % was calculated as (maximum – minimum) / mean. Over the particular 5000 faults that were simulated to achieve the data shared for the paper, the local vPAC system = (22.09ms – 16.85ms)/19.45ms = 26.9% while the local microprocessor relay = (26.07ms – 18.98ms)/20.74ms = 34.2%.

Testing iterations were repeated continuously over multiple weeks to ensure the vPAC performance did not degrade. Results remained consistent with what is being present here, throughout the highly accelerated stress screening.

The findings here were used to improve the existing field vPAC pilot SRP has in place, featuring 87L protection on a 69kV sub-transmission line. The Layer 3 vPAC topology is in place there and is awaiting its first system fault to occur since commissioning in March of 2025.

Conclusions & Future Work

The results of the accelerated stress testing conducted in the Salt River Project (SRP) Technology Innovation laboratory confirm that the SSC600-based virtual protection system (vPAC) delivers reliable and consistent performance for line differential (87L) protection applications.

Across a wide range of fault types, locations, and communication scenarios, the vPAC architecture consistently outperformed traditional microprocessor-based relays in round-trip response time, with lower variance and high stability over prolonged testing periods. These findings validate the viability of centralized and virtualized protection architectures in real-world utility environments and support the broader adoption of vPAC for critical protection schemes.

Biographies:

Brant Heap is Director of Protection, Automation and Control at Salt River Project (SRP), a community-based not-for-profit utility serving more than 2 million customers in central Arizona. With over two decades of experience in the electrical industry, Brant leads the transformation of SRP’s protection, automation and control systems to support a smarter and more resilient grid that meets growing customer demand. He is guiding SRP’s substation virtualization initiative, a foundational element of the utility’s digital evolution. Beyond SRP, Brant is shaping the future of the industry as Chair of the vPAC Alliance (Virtual Protection, Automation and Control), advancing secure, open and interoperable architectures that redefine how utilities deploy protection, automation and control technologies.

Anthony Sivesind (P.E., M.Sc.E, B. Sc.EE) is owner of a U.S. engineering firm and has 20+ years’ experience in the utility industry, working in a variety of roles. He has led new protection and control initiatives at SRP, along with standards development and implementation. He also spent time as a solutions architect at VMware, learning and creating new products with industry partners. He now acts as a consultant to help navigate grid transformation through the advancement of operational technology. He participates in IEEE and IEC standards development and chairs the Software Working Group of the vPAC Alliance.

Marco Nunes has held different positions at ABB Switzerland before becoming a Global Product Marketing Manager for ABB’s Distribution Solutions, Protection & Control Products. In 2024, he got appointed as Head of Grid Edge & Cloud analytics for Digital Substations. He has a BSc in Electrical Engineering/Power Systems from the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, a Swiss Federal Diploma of Commerce and a Postgraduate Diploma in International Business Management from the University of Cumbria in UK.